|

|

First Interview —

Peter Anastas with Karl Young

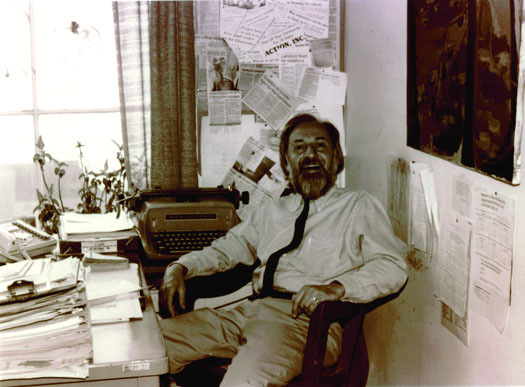

Peter Anastas at Action, Inc. 1985

Interviewer's Introduction and Guide to Format and Organization

This interview begins with a brief biographical summary in italics. I

initially asked Peter several questions in a single paragraph, and we

broke that into parts. Since these and most other questions are short, we've

rubricated the questions so they can be used as guides to the interview. The

interview is long by current standards, and we'll do at least one more. The

rubricated questions should make it easier for readers to find passages that interest

them most. I generally don't do much but ask simple questions. On the few occasions

when I become a little more expansive, I hope the reader will indulge me, and still find

the presentation more manageable than interviews with lengthier questions. I've

reserved most of my editorial comment for the following paragraphs of this introduction.

In some places the questions act as subject heads for longer divisions in the interview.

In other places, they act as subdivisions. When they act as major divisions, a score precedes them.

Peter Anastas likes the interview format. This shouldn't be a surprise, since he has worked

extensively as an oral historian. Interviews have also been an essential part of his profession

as a social worker; and public speaking has been just as essential to his commitment to activism.

At the same time, it is interesting and important to me to note how much of his conversation

makes constant reference to what he reads, suggesting a profound integration of

reading with other activities, which some see as inherently different during this phase of history and

media evolution. It also seems important to me how broad-ranging and free from dogma or bias

his reading has been. One of many ways you could see parts of this interview is as a description of

a long apprenticeship as a writer through reading, performing a partly subliminal criticsm in the

process, and watching language in action — as he used it with the writing of others in his mind,

as he used words himself, as he heard others speak and write, and as he saw the results of such

usage of language. As a running commentary on the role of reading in engaged circumstances: an

application of extensive reading to active life in the heart of a vibrant, if often troubled, community,

Peter's remarks carry more weight than they might under other circumstances.

This helps emphasize several themes in this survey in addition

to the simple presentation of Peter's work as a writer. (I'm certainly not minimizing

that: I published his first major work, "A Disturbance of Memory on the Acropolis,"

in 1972, at a time when a number of these considerations had not taken shape, and,

perhaps curiously to younger readers, we both took a number of social issues

for granted.) Clearly, Peter's "bookishness" didn't get in the way of his social activism,

nor did reading or discussion of what we read act as a substitute for action. In fact,

his activities in the daily lives of his clients as a social worker, and his social and

political activities not only began with reading, but reading and activism did not

lose their interdependency during the decades that followed.

"Role models" have been an essential part of American discourse for decades, and commentators

tend to identify "the millenials," those who have come of age in the last decade (fairly

or not), as more socially conscientious and more responsible than the "generation X"

which preceded them. I would like to see Peter as a forerunner of those who turned

to various forms of social service in the last decade when public demonstrations and

other earlier forms of activism had been effectively suppressed. I'd also like to see him

as an example for the millenials to contemplate, as some of them begin or bring

coherence to their adult lives. It is important not to mislead young people into believing it is

easy to maintain multiple careers. Those who can simultaneously maintain the discipline and

practice necessary to becoming a fully developed poet or novelist while seriously practicing another

demanding profession, be it teaching or social work, are rare. But if young people run into the

wall of responsibility to family and the desire to live a comfortable life while writing, there

are ways they can put their reading to use elsewhere — and perhaps they'll have a decade

to learn basic writing habits which allow them to maintain their skills, collect material, and begin

their most active period of writing after retirement, as Peter has done. Although not given to

complaints, Peter has at times seen his creative life broken, and several decades lost. We can't

know what he would have done if a frivolous law suit had not killed his first major project, and

forced a change of direction. But it may be that the decades of what we might call creative interuption

or extended preparation may have given him — and us — unforseen benefits.

At the same time,

particularly in Charles Olson's centennial year, it seems important to note that Peter's most

important mentor could live in abject poverty and with extreme personal eccentricities,

but still be able to adamantly and unflinchingly carry on the generally unglamorous civic activities

of local politics, from fighting to maintain wetlands at a time when virtually no one in the community

was concerned with environmental issues to the immediate needs of housing for those with

low or no income. AND how he still exerts an influence on local politics, despite the fact that

he, too, went through periods when not only Gloucesterites, but even the writers whom he most

influenced, ignored or belittled what he had to say.

— Karl Young

Peter Anastas was born in Gloucester, Massachusetts in 1937. He attended local schools, graduating in 1955 from Gloucester High School, where he edited the school newspaper and was president of the National Honor Society. His father Panos Anastas, a restaurateur, was born in Sparta, Greece, and his mother, Catherine Polisson, was born in Gloucester of native Greek parents.

Anastas attended Bowdoin College, in Brunswick, Maine, on scholarship, majoring in English and minoring in Italian, philosophy and classics. While at Bowdoin, he wrote for the student newspaper, the Bowdoin Orient, and was editor of the college literary magazine, the Quill. In 1958, he was named Bertram Louis, Jr. Prize Scholar in English Literature, and in 1959 he was awarded first and second prizes in the Brown Extemporaneous Essay Contest and selected as a commencement speaker (his address was on "The Artist in the Modern World.") During his summers in college, Anastas edited the Cape Ann Summer Sun, published by the Gloucester Daily Times, and worked on the waterfront in Gloucester.

After graduating from Bowdoin in 1959, Anastas lived in Florence, Italy until 1962, where he studied medieval literature at the University of Florence and taught English at the International Academy. While in Florence, Anastas worked as an interpreter-translator at the university's Institute for Physical Chemistry. His translation of Prof. Giorgio Piccardi's The Chemical Basis of Medical Climatology, was published in the U.S. in 1962.

Returning to Gloucester in 1962, Anastas taught English at Rockport High School and Winchester (MA) Senior High School before winning a graduate teaching fellowship to Tufts University, where he studied English and American literature, receiving a master's degree in 1967 with a thesis on the concept of place in the works of Henry David Thoreau.

Between 1967 and 1972, Anastas worked as a free-lance writer, publishing his first book, Glooskap's Children: Encounters with the Penobscot Indians of Maine (Beacon Press, 1973), with photographs by Mark Power. As a result of his experience of poverty in rural Maine, in 1972 Anastas joined the staff of Action, Inc., Gloucester's antipoverty agency, where for thirty years he was a social worker and Director of Advocacy & Housing. For twenty years he was also an adjunct faculty member at North Shore Community College, where he taught English and literature.

During these years Anastas continued to write and publish, contributing a weekly column, "This Side of the Cut," to the Gloucester Daily Times and publishing When Gloucester Was Gloucester: Toward an Oral History of the City (with Peter Parsons and photographs by Mark Power), SIVA DANCING, A MEMOIR, Landscape with Boy, a novella in the Boston University Fiction Series, and Maximus to Gloucester, an annotated edition of the letters and poems of Charles Olson to the editor of the Gloucester Times. In 2002, At the Cut, his memoir of growing up in Gloucester in the 1940s, was published by Dogtown Books; and in 2004 Glad Day Books, founded by authors Grace Paley and Robert Nichols, published Broken Trip, a novel of Gloucester in the 1990s. His most recent novel, No Fortunes, set at Bowdoin College and in Gloucester in 1959, was published in 2005 by Back Shore Press, a writers' collaborative, which Anastas co-founded. Anastas has also published fiction and non-fiction in Niobe, The Falmouth Review, Stations One, America One, The Larcom Review, Polis, Split Shift, Cafe; Review, Sulfur, Process and Minutes of the Charles Olson Society.

Anastas is the father of three, Jonathan, an advertising executive in Los Angeles, Rhea, an art historian currently teaching at USC, and Benjamin, a writer who has published three novels. Having retired from social work in 2002 to devote full time to writing, Anastas continues to live in Gloucester, where he is an activist for waterfront preservation and sustainable development.

What were some of your early influences and interests? Let's start with one of your annotated bibliographies, in biographical format.

Steinbeck and Hemingway had a great impact on me in high school, along with my early reading of science fiction in 7th and 8th grade, beginning with Jules Verne, when I was twelve years old, and ending with Walter M. Miller's post-nuclear holocaust novel, A Canticle for Leibowitz, which I read eight years later, a narrative of intellectual survival I've never been able to forget. I can trace the evolution of my political consciousness back to Grapes of Wrath and my readings in science fiction, Scientific America and popularly written books about Relativity and Quantum Theory constituted the beginnings of my lifelong interest in the world and its workings.

But let me go back to the beginning. I don't ever remember not having books in my life. Each night at bedtime my mother read to my brother and me from Thornton Burgess, the Babar books, Wind in the Willows and the Peter Rabbit series. At the age of five, I taught myself to read. I had picked up the rudiments in kindergarten when I was four; by the time I was in first grade there was no stopping me. My Aunt Helene, who was an elementary school teacher, got me my first library card when I was six years old. This began a lifetime of browsing among what were once the amazing resources of the Sawyer Free Library.

The first books I got out of the library were the Oz series. Once I was in school studying geography and history, I became fascinated with Native American culture. I'd always known about the aboriginal presence in Gloucester and the legend that Vikings touched upon our shores, perhaps even wintering along the Annisquam and Little Rivers near West Gloucester. Elliott Rogers, a family friend who was a local historian and amateur naturalist, told me stories of the town's settlement in 1623 by "planters" out of England's West Country. My first sight of his collection of artifacts from the paleo and archaic periods of Indian inhabitation initiated a lifelong interest in these peoples, and I began to read everything I could find in the library about how Indians lived and what they made. The Holling C. Holling books, with their beautiful illustrations, opened windows to me not only on Eastern and Adena cultures but on the earliest inhabitants of the entire North American continent.

When we studied "Cave Men" in school, prehistory also held me. This led to a subsequent passion for the Ancient Egyptians and the Greeks. I found books for young readers about Egyptian religion and the Peloponesian wars, yearning for the time when I would turn fourteen and be allowed to use the adult section of the library. Meanwhile, teachers lent me more advanced texts or my mother or aunt would borrow what I wanted from the main library using their own cards.

This was when I fell in love with mythology and devoured the Bullfinch books recounting Greek and Roman myths and legends. At the same time, I read about the settlement of the American frontier, about pioneer life, always with an eye on how people survived, how they got their food and cooked it, how they built houses and raised crops. I became fascinated with process and the records of daily life among the various peoples of the earth.

Although I remember a wonderful thick, green, clothbound book of illustrated short stories Aunt Helene gave me when I was recuperating from an attack of the mumps, I can't recall reading much fiction until sixth grade when we were assigned books in the Illustrated Classics series, including Cooper's The Last of the Mohicans and Stevenson's Kidnapped. N. C. Wyeth's dramatically colored illustrations established ur-images for me of Cooper's characters, bringing woodsmen and Indians to life in a way that was only rivaled by images in the movies we saw each Saturday afternoon at the Strand and North Shore theaters on Main Street, beginning with the last years of the Second War.

In seventh grade a new interest in science, cultivated largely by my teacher Lovell Parsons, sent me not to science books at first but to science fiction. After reading my way through Jules Verne and H. G. Wells, I began reading Ray Bradbury's Martian Chronicles along with some of contemporary sci-fi and fantasy novels of the time like L. Sprague De Camp's Genus Homo and John Wyndham's The Day of the Triffids. Novels like these seemed to satisfy my need to understand how science entered our lives and my curiosity about social relations, especially sexual ones. I still read simplified versions of Einstein's theory of relativity, devouring each monthly issue of Scientific American even though I barely understood the technical articles. But reading adult science fiction novels helped me find answers to the things I was beginning to ask myself like, where do we come from and what does life mean? Encountering what was then called "the love interest" in those novels provided analogues to the things I was feeling about my body and this helped me to understand what the crushes I was getting on girls meant.

By high school I was reading serious fiction, not simply the novels we had been assigned to read by Dickens or George Eliot, but all of Steinbeck and Hemingway I could get my hands on. I read an occasional best-seller like The Caine Mutiny; but mostly I stuck to the classics of the 19th and early 20th centuries. I didn't discover these books by myself. As I've described in my memoir Siva Dancing, it was my chance meeting with a young woman painter after our family moved from the Boulevard to Rocky Neck in 1951 that opened the world of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky to me, along with the novels of Thomas Wolfe that overwhelmed me with their torrents of feeling.

Virginia Whittingham was a contemporary artist, barely out of school herself. I met her at the counter of my father's luncheonette and S. S. Pierce grocery store, where I began to work during the summer between Central Grammar and Gloucester High School. When she learned that I loved to read, expressing an amazement that I was trying at that time to get through Zimmer's Philosophies of India, Virginia wrote out a list of novels she thought I might enjoy. It included Anna Karenina and Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment, The Idiot and The Brothers Karamazov, all of which I eventually read with immense pleasure and interest. Virginia's list also included American novelists like Dreiser, Sherwood Anderson and Thomas Wolfe. Perhaps today it might not be possible to understand the impact on a thirteen year old boy of these texts. Quite literally they changed my way not only of looking at the world but of being in it. Reading the novels Virginia had suggested made me the person I am today, and though I never saw or heard from her again (if she's still alive I suspect she would be in her eighties) I cannot begin to say how grateful I am to her for taking the time, those many years ago, to write out a simple lists of books for a boy to read, books that changed his life. With her long, ash-blond hair, Virginia was stunningly beautiful, and a fine painter. Discussing art with her throughout an entire summer started me on another lifetime fascination with the visual. Naturally I had a crush on her, but I've already written about that in my memoir Siva Dancing.

The novels I began to read that summer before high school and the ones I continued to read throughout my secondary education were crucial to me; but there is another source of my reading that is equally significant. That was the Book Find Club, founded by the progressive publisher George Braziller. I first joined the club in 1951, when I saw a membership offer advertised in Scientific American. It was the usual book club offer — if you bought one book and joined the club you got another book or two free. To me, who was just beginning to collect books, this seemed like manna from heaven. Also, the titles of the books intrigued me. Many were scientific; in fact, I began my membership with W. P. D. Wightman's The Growth of Scientific Ideas and George Gaylord Simpson's The Meaning of Evolution, both from Yale University Press. But the club also offered literary titles along with its list of political, sociological and philosophical books, all of them new.

It was through the Book Find Club, which I was later to learn had been investigated by the House Un-American Activities committee for offering its members "subversive" books,

that I began to branch out in my reading. Henry Steele Commager's attack on McCarthyism, Freedom,

Loyalty and Dissent,

was probably my first foray into political analysis. I also read C. Wright Mills' White Collar, along

with Emanuel Velikovsky's Worlds in Collision (the renegade psychiatrist's assertion that life on

this planet sprung from living matter brought to earth by crashing asteroids, much abused until recently,

may well be proven true by the discovery of microorganisms in asteroids found in Antarctica

and suspected to be from Mars.)

This may seem like heady reading for an adolescent; but I had nearly ten years of practice behind me when I first opened the pages of these attractively designed books, which arrived regularly each month. I was responsible for scarcely more than $1.98 in costs if I didn't return the announcement card in time. But I wanted the books — I could certainly afford them out of the small salary my father paid me each week. I wanted them to read and I wanted them to stand side by side in the antique Victorian bookcase my mother had bought for me at an estate auction. I was beginning to love books for themselves as much as for what they contained.

Other books of significance that I got from the club were Carlton Coon's The Story of Man and C.W. Ceram's Gods, Graves and Scholars. Although I would later reject Coon's racist anthropology, his was the first book that gave me a systematic sense of how we came "up from the ape," in the words of another Book Find author, Ernest Hooten. Ceram's book, however, opened up an entirely new avenue of interest for me in archaeology and ancient languages, combining my prior fascination with Egyptian and Greek origins with a glimpse into Central American cultures that I knew little about. Ever since, archaeology has been one of my chief loves.

I've said that the club also offered more purely literary texts, including autobiographies like Sean O'Casey's Sunset and Evening Star. It was through the club that I discovered the stories of J. D. Salinger and The Catcher in the Rye. I suspect that these two books were among the first literary fiction by living authors I read beyond Hemingway's The Old Man and the Sea and Steinbeck's East of Eden, both published when I was still in high school (I reviewed The Old Man and the Sea for The Beacon, the school's literary magazine). Reading Salinger helped me see that I, too, could write about growing up, using the language that people employed in daily life and not the formal rhetoric we were subjected to in the reading we did for our English classes.

There must have been some dissonance for me then, perhaps a conflict between the demands of the classroom and its more traditional texts and the reading I did on my own that took me right into the heart of my own times — the politics, the literature, the sociology and science. In retrospect, I think I managed the separation because I had always considered my own private reading to be more important than what was assigned to us in school. I did my assignments, and I was a pretty good and competent student; but my real life was always in my own books and in the pursuit of those interests that were never satisfied by any school.

Still, I don't mean merely to list the books I read in high school that had such an influence on me. What I want to do before I speak about my college reading is to note that encountering these books helped me to establish and explore the social and intellectual themes I continue to pursue today; they helped to lay the foundation of the life of my mind. I've never stopped reading in ancient history and archaeology or in science, particularly neurobiology and physics; I still read in politics and political science, even in sociology, although much less than I did in the 1960s. All this was made possible though a simple advertisement in Scientific American that led me to the Book Find Club, and those books that helped me move from adolescence into the adult world of ideas.

In college I began the systematic study of literature. Many of the books that were assigned to us for class were also books that had a profound influence on me, although I continued to read on my own even more than I had done so previously. This was made possible because the Bowdoin College library was everything one sought in a library. I can't recall ever being unable to find any book I wanted in that vast collection. Through an aggressive acquisition policy the library also kept up with contemporary British and American writing, so that I was able early on to read such Beat classics as Clellon Holmes' Go and novels by the Angry Young Men of Britain like John Wain's Hurry on Down and Kingsley Amis' Lucky Jim. It was also at this time that I began eagerly to devour the early volumes of Lawrence Durrell's The Alexandria Quartet as each appeared. Sadly neglected today, their exquisite prose inspired many of us to become writers, indeed, to travel beyond the narrow literary and intellectual confines of America.

The first two books we read in novelist Stephen Minot's freshman composition course during the fall of 1955, Thoreau's Walden and Sarah Orne Jewett's The Country of the Pointed Firs, have remained books that I return to constantly. Reading Thoreau for the first time, beyond excerpts in our high school textbook on American literature, helped me to understand my own need for solitude and my deep connection with the natural world. Jewett, whom at first I resisted because of her subtlety, became the first localist who caught my attention, nurturing my love for a Maine landscape I would respond to for the rest of my life and showing me how one might write about one's home country.

While these books had some immediate meaning for me, it was later in life that I would find their resonance of deeper importance. But the books which had the greatest impact upon me were those I discovered for myself in the library and in the remarkable off-campus bookstore operated by Carl Apollonio, a Korean war veteran and history major, who had returned to college on the GI Bill. At Carl's I literally found the books that were to have the profoundest intellectual influence on me, including books by Walter Kaufmann and William Barrett about the Existentialists that changed the shape of my life and set me on a personal and philosophical journey that continues today.

I can't begin to describe the impact on me of first reading Sartre's Nausea in that early New Directions cloth bound edition, which I still possess. Other students were reading Camus in the classroom by then and I read The Stranger, The Plague and The Fall with absorption, later picking up his philosophical essays, The Myth of Sisyphus and The Rebel, which had just been issued in the Vintage paperback library. But it was Sartre's grittier vision of alienation that I ultimately connected with, reading everything I could find in English by him and straining my elementary French to comprehend the original when no translations were available. This is not the place for a digression on Sartre's philosophical and political influence on me. Let me simply indicate that of the handful of writers and thinkers who have shaped my own mind, Sartre is among the foremost and remains so today.

I should, however, add a note about the paperback explosion that happened just about the same time as I entered college. Although by high school I owned a few books in the Mentor paperback series, notably E.V. Rieu's fine prose translation of The Odyssey and Ortega Y Gasset's The Revolt of the Masses, which I had picked off the magazine rack in my father's store, I had not begun to purchase other inexpensive editions of classics that were becoming readily available then. What started me on the creation of my paperback library was my purchase during the summer between high school and college of C. Day Lewis's wonderfully readable translation of The Aeneid in the Anchor Books series, which I had just studied in my fourth year Latin class.

I bought that book at a little bookshop in Rockport, Massachusetts called The Mariner's Bookstall. I mention it because, along with Brown's Book Store in Gloucester it was the only bookstore I knew. And Mariner's began to stock copies of most of the new paperback imprints that were then coming on the market, including Anchor Books and the Vintage series. To be able to buy a classic for as little as eight-five cents was a tremendous gift for young people like me, who were just getting started collecting and reading books. And once I was in college I doubt that a day went buy during my first year or two when I wasn't in Carl's bookstore picking up yet another translation of Homer or Dante or deep in discussion with Carl or certain members of the group of local artists and intellectuals who lived in and around the college community. We talked about Sartre, of course, and Spengler; we read and discussed the new fiction that was beginning to come out of England, novels by John Wain and John Braine, by Kingsley Amis and Alan Sillitoe. And of course we debated the Beats endlessly. I'd read Kerouac and Ginsberg by then and was utterly in the thrall of the Beat rebellion (see my blog essay on the 50th anniversary of Kerouac's On the Road: http://peteranastas.blogspot.com/2007/10/on-road-fifty-years-later

Slowly I amassed a library of books, many of which I still own. By the time I entered college I had stopped my membership in the Book Find Club, which soon ceased operating. Carl gave me a discount on whatever I bought from him. And what I bought was mostly paperback editions of books of such diverse subject matter as Loren Eiseley's The Immense Journey and Zeller's Outlines of the History of Greek Philosophy. Naturally I overspent my budget, which consisted of the money I earned during the summer and an "allowance" my parents sent me regularly to help with extra expenses. Needless to say those "extra expenses" were generally for books, for I had little else to buy at the time. By sophomore year I was earning pocket money playing piano during the weekend in a small dance band at the Officer's Club of the Brunswick Naval Air Station and working at the library, where I continued to work through the rest of my college career, not only because of the pay but also because it gave me unlimited access to more books.

Looking back on my reading between 1955 and 1959, my undergraduate years, I can only say that it was not uncommon for me to read a book a day, many of them not required for any course I took. Certainly I read books that my professors in English, history and philosophy, or in the Greek, Latin, French and Italian literature I also studied, suggested as outside reading. Titles that come to mind would be Lionel Trilling's book on Arnold or certain volumes in Toynbee's great series (which I've never finished). I also read Clive Bell on the post-impressionists and Herbert Read's ground breaking essays on Cubism and Surrealism in The Theory of Modern Art.

Then there were the poets we studied in class and those we read on our own — Rimbaud, Verlaine, cummings, Pound (a special favorite), Stevens and later the Beats. And the modernist novelists who came to mean so much to me: Joyce, Proust, Thomas Mann, Kafka, Celine. There were books like Arturo Barea's memoirs of the Spanish Civil War and Hermann Broch's the The Death of Virgil, books I came across in my wanderings through the library stacks on idle afternoons or late nights when the library was closed and I had its treasures all to myself. These are books I pick out of my memory or as I walk past one of my book cases and catch sight of the actual volume I bought in those years, books like The Recognitions by William Gaddis or John Rechy's City of Night. They also include Colin Wilson's The Outsider, LeComte du Nouy's Human Destiny and Denis de Rougment's Love in the Western World, books that our teachers disparaged but that some of us read with interest and excitement. To this day certain eccentric writers or visionary thinkers, like Leo Stein or Marshall McLuhan, not to speak of the great individualists like Henry Miller, continue to hold my interest. It is the rebel in me that attracts me to them and the fact that I take what I need from the books I read no matter what the received critical opinion or judgment might be.

Speaking of rebels, my political education began not with Marx but with John Dos Passos' USA, which had been assigned to me in a seminar on American writers required for English majors. Reading Dos Passos I first became acquainted with native radicals like Randolph Bourne, whose essays on war and cultural renewal had a profound impact upon me. And my continuing induction into the most contemporary and avant-garde writing was through the pages of the Evergreen Review, where I discovered the works of Samuel Beckett and the philosopher E. M. Cioran and rediscovered Charles Olson, the poet who was living in my home town at the very moment I read his seminal essay, "Human Universe" in the review.

I should also mention the profound influence upon me of D. H. Lawrence, particularly during my last two years in college when I chose to write my senior thesis on Lawrence and myth, concentrating particularly on his Mexican novel, The Plumed Serpent. Introduced to Lawrence in Lawrence Sargent Hall's course in modern literature, I began to read everything by him I could lay my hands on, even a splendid copy of the original 1928 Florence edition of Lady Chatterley's Lover, housed in the rare book room of the library. But it was not the sexual in Lawrence that attracted me so much — after all, I had read Miller's Tropics in the Obelisk Press editions friends had brought back from France. What I loved in Lawrence was his evocations of places in the world, his north of England, Italy and the American Southwest, which I would later travel to myself literally because of the way Lawrence had described New Mexico. I was also attracted to Lawrence's life, to the way he and Frieda traveled like Gypsies from place to place, the way he appeared to write effortlessly at the kitchen table while dinner was being prepared, the way he seemed to penetrate the psychology of human relationships, which I had long puzzled over and began to write about myself in my first attempts at a novel. Lawrence seemed then to me the very model for the kind of writer I wished to be, itinerant and urbane like Hemingway, a linguist like Pound, an expatriate; for I had also read the major Lost Generation writers, Fitzgerald, McAlmon and their precursors in Paris like Gertrude Stein, and the option of living outside of one's country and culture seemed a compelling one.

Lawrence, the working class intellectual, who was alienated both from his own class and from the culture he grew up in, along with the literary society that should have provided a sustaining environment, attracted me deeply, not only as a writer but as a person, restlessly moving from Nottinghamshire to Germany, from Italy to Ceylon, Australia and the American Southwest, ultimately dying in the South of France. The Lawrence who also interested me was the Lawrence who wrote, "At times one is forced essentially to be a hermit," adding: "Yet here I am, nowhere, as it were, and infinitely an outsider."

My deep study of Lawrence in my solitary room on 83 Federal Street, during my final year in college, prepared me for the senior thesis I was expected to submit as partial fulfillment of the graduation requirements for an English major. I chose The Plumed Serpent, not one of Lawrence's most successful or highly acclaimed novels, but one which interested me because of its mythic substructure. For as a student of Dante I was also interested in myth and symbol and the creation of anagogic structures of belief.

By, then, I was already pointed toward Europe. Lawrence's travel books on Italy and

Sardinia delighted me. I also read Carlo Levi's Christ Stopped at Eboli and Words

Are Stones in translation and Paura della Liberta`, his book about the myth of

fascism and the fear of the terrible responsibility of freedom that attracts people to

authoritarian regimes, in the original. Levi, a physician, writer, painter and political activist,

seemed yet another example of the urbane, multi-faceted European intellectuals I found so

attractive. Levi's descriptions of Italy during and after the war drew me to the country as a

whole, just as reading Dante had drawn me in particular to the city of Florence.

I suspect the turn to Europe was already implicit the moment I read Sartre. I knew that my genetic and intellectual roots lay there. It was only a question of how to manage the trip with military service hanging over my head. An announcement posted in the library from the University of Florence offering courses in Dante and Renaissance culture and history in Italian to foreign students caught my attention. I applied and was accepted. So long as I continued to be a student I would be exempt from the draft.

Ironically, it was not in Italy but in my own neighborhood that I first learned about the single most important Italian writer of my life. During the summer before I left for Europe I befriended a young Italian graphic artist named Emiliano Sorrini, who had come to Gloucester to work with the painter Leonard Creo before moving on to New York, where he hoped to settle with his American wife. When Lenny introduced me to Emiliano it was with the hope that we could exchange language lessons with each other. Of course I jumped at the opportunity to practice my spoken Italian, and Emiliano whose English was already good proved to be a challenging student. Like many of the Italian artists I would later meet, Emiliano was also a reader — indeed, he was an intellectual with a deep understanding of the major political and cultural issues of the time. He had met Alberto Moravia and he knew Carlo Levi personally. But his favorite contemporary Italian writer was Cesare Pavese, of whom I knew nothing.

"If you love Moravia," he told me, "you will die for Pavese." And he advised me not to seek out translations in English, which he had been told were poor, but to wait until I arrived in Italy to buy and read Pavese in the original.

As soon as I arrived in Rome — even before I looked Lenny up in his studio on the Via del Babuino — I visited a nearby bookshop and bought my first Pavese novel, the violently neo-realistic Il Compagno, thus initiating one of the profoundest literary and intellectual experiences of my life. Once I was settled at the Pensione Cordova on Via Cavour in Florence, I went out and on the strength of that first novel bought all of Pavese's works in print, that is everything he had published.

Thus began another of those divided experiences for me. While I studied Dante, Medieval literature and Renaissance culture at the university by day, I read the poems, stories, essays, diaries and novels of Pavese by night. By the time I had arrived in Firenze, just at the time of my22nd birthday on November 15, 1959, my Italian reading comprehension was good. But after a few months of classroom lectures, almost nightly film going, conversations with fellow students and friends in the pensione, not to mention my daily readings of newspapers and magazines, I was able to read Italian practically without the help of a dictionary. I will have more to say about Pavese, when we speak about my time in Italy and about my political education.

Let's start with some major concentrations. What was important to you about reading Pound and studying Dante?

It was Pound who led me to Dante, and that journey began when I was 18 years old, a freshman in college. As a high school student I knew very little about contemporary verse. It wasn't taught in our literature courses, and what I had come up with in my browsing at the library was Whitman's Leaves of Grass, a couple of volumes by Amy Lowell and some poems by Yeats I wasn't yet ready for. Up to that point, the only living poet whose name I knew was Robert Frost. Frost came to Gloucester to speak as part of the Cape Ann Festival of the Arts when I was in high school, and I later met him at the home of Hyde Cox, the president of the Historical Association and a long-time friend of Frost's. We'd read Frost in eighth grade, the usual chestnuts (not unfortunately "After Apple Picking" or "Neither Out Far Nor in Deep," which later excited me); and when I met him face to face I found him repetitive, though I admit to being impressed by his fame and the fact that I, a small town boy, was actually in his company. I was playing jazz and beginning to listen to avant-garde music — Schoenberg, Berg, Webern, some early Elliott Carter — and I was looking for poetry that moved me like the music or the abstract art I was experiencing on Rocky Neck, in East Gloucester, where we had moved in 1951 after my father opened a luncheonette and S. S. Pierce gourmet grocery store. Rocky Neck was America's oldest art colony. At the time we lived there, a number of fine contemporary artists spent their summers painting not far from our house and my brother and I wandered frequently into their studies and galleries and were befriended by them.

It was in one of those galleries that I actually discovered contemporary poetry. Just down the street from our house ceramicists Kalman Kubinyi and his wife Doris Hall owned a gallery and coffee house. Along with their own work and the paintings they exhibited by artist friends, they had a number of literary magazines and reviews spread out for sale on a table. Among them was the first issue of Four Winds, a little magazine of poetry, prose and visual art that had just been published in Gloucester, edited by Vincent Ferrini and his wife Margaret. I snapped it up immediately and took it home, thus beginning my apprenticeship in modern poetry.

That first issue, which I still own, featured a Maximus poem by Olson, which I couldn't understand, along with poems by Robert Creeley, Denise Levertov, Cid Corman and Ferrini himself that I found both intelligible and exciting. There were a couple of marvelous oblique short stories and reproductions of paintings and drawings, one by the Paris-born Yugoslavian artist Albert Alcalay, who would soon begin spending summers on Rocky Neck with his wife Vera and sons Ammiel and Leor. And it would be Albert who would later introduce me to the most innovative contemporary painting, while pointing me to European avant-garde writing as featured in Botteghe Oscure, the international literary review published in Rome by Marguerite Caetani and highlighting such writers as Giorgio Bassani, Umberto Saba, Eugenio Montale, Carlo Levi and Ewe Johnson that would later be of great importance to me.

Reading Four Winds sent me to Ferrini's picture framing shop, located not far from Rocky Neck, in a shed on East Main Street at the rear of the building Vincent later made his home in. Late one afternoon in early September, on my way home from school, I poked my head in the door and a welcoming face turned from the table saw. Eyes lit up, the saw was shut off, and I received the first of thousands of strong handshakes I would be getting from Vincent the rest of my life.

I told Vincent I'd been reading Four Winds and I was interested in poetry. When he asked me who I was reading, I could only come up with names like Whitman and Yeats.

"Yes, yes," he said, not impatiently, "but who are you reading who's living — who's alive?"

I was at a loss for words.

"Let's begin," Ferrini said, grabbing some volumes down from what I observed were shelves stuffed with books of poetry.

That day Vincent introduced me to the early imagist work of Ezra Pound, to Williams' Paterson, and I began to visit him regularly to talk about poetry and about life. He never asked my name initially. It was first things first with Vincent, then as always; and poetry was Number One.

Later it turned out he knew my father; and even later we talked about our common roots in the Mediterranean, his in Italy, mine in Greece.

Still, I will never forget those early years of our friendship, when I was in high school and Vincent was so accessible, a storehouse of information about poets and poetry on my way home from the very place that was supposed to teach me about those subjects but only ended up boring me.

When I got to college I immediately began searching through the library and the bookstore for new poetry. I bought cummings' i: Six Non-Lectures at Carl's bookstore and learned from cummings about the poets, both ancient and modern, that had shaped his art. I also bought Pound's Personae and Cantos (I still have both volumes). I was getting a small weekly allowance from home for laundry expenses and, as I've said, I would shortly begin earning a couple of dollars playing jazz and cocktail piano weekends in local bars and at the Officer's Club at the Brunswick Naval Air Station, close by the campus. All that money went into books, as my money still does today, fifty years later.

While I can't claim to have instantly understood Pound, I knew from the few poems Vincent had read to me that I was in the presence of important poetry. More than that, I knew Pound was the kind of writer, the kind of mind, I resonated with, as I was later to become close to Olson. I was reading Catullus in Latin class and Pound's versions of Propertius excited me. I was also drawn to Pound's mastery of languages and to his absorption in Medieval literature. I soon discovered The Spirit of Romance, which led me to Dante.

I bought the Portable Dante and began my first reading of the Commedia, resolving

to study Italian, which I did, two years later, finally reading Dante in the original with Jeff Carre,

my Italian professor, who had read Dante with Charles Singleton. I'll never forget those

extraordinary afternoons in Jeff's office when just two of us sat down with him for nearly a year,

reading our way excitedly from the Sicilian School and the Stil Novisti through the entire

Commedia, practically line by line.

By that time, it was clear to me that in order truly to understand Dante I had to immerse

myself in the very ground of his opus, the city of Florence and its history. I decided to travel to Italy

after graduation, to study Medieval literature at the University of Florence. My decision was based

almost entirely on my interest in Pound and the fact that he had lived for so long in Italy and also

on my readings of Hemingway's Italian stories and

A Farewell to Arms. Equally, my reading in the Lost Generation writers and their lives in

Paris during the 1920s, coupled with my own growing sense of alienation from my own country,

kindled a desire on my part to experience the same kind of expatriation that had fueled the

experimental work of Pound and Hemingway's powerful early stories. I felt I needed to get out of

America and away from my family.

I'd studied Italian to better understand the quotations in Italian in Pound's Cantos,

just as I studied Greek and later, in Italy, Romance Philology. I never became a Pound scholar, though

I did visit Pound in September of 1960 at his son-in-law's castle, Schloss Brunenberg, with my friend,

Peter Denzer, who was writing a novel based on Pound's exile in Italy. It's was Pound's life that

drew me as much as his poetry, and of course by then I had plunged deeply into the stream of

Modernism. As much as I loved his poetry, Pound's fascist politics disturbed me, especially after

I'd met Olson, who filled me in on the broadcasts Pound made from Rome radio during the war.

And once I was living in Italy and had met people who'd known Pound it was clear that fascism

for him had not been an aberration but a deeply held belief, though in our brief encounter in that

castle near Merano Pound said little. He and Peter talked of mutual friends like James Laughlin,

who'd finessed Peter's visit to Pound, before Noel Stock, Pound's biographer and gate-keeper,

ushered us out of the medieval castle that dominated the valley. It was late September and I

remember that the vendemmia, the grape harvest, was underway and all around us, as we

made our way from the castle back up the hill to the gasthaus, where we were staying, were

these enormous wooden barrels of white grapes on wagons drawn by oxen out of which the superb

pino grigio wine of the Alto Adige would be made. By the time I had found him, Pound was an

exhausted old man, who had effectively taken a vow of silence, though the Pisan Cantos would

continue to blaze their way through my mind.

At the university in Florence I attended lectures on Dante and his times by the great humanist scholar Eugenio Garin. I also took courses in Medieval literature and Renaissance art and history. But it was the living breathing contemporary Italy, where Dante's dialect could still be heard in the ancient neighborhoods of Florence, that drew me — the politics in the street, as young communists clashed with neo-fascists, the explosiveness of Antonioni's films, Pasolini's novels and films, and the astounding abstract paintings of Vedova and Scanavino — coupled with fact that as soon as I was away from home all I wanted to do was write, not only about what I had left behind but what I was experiencing daily. Relegating my studies to a few mornings a week, I got a job teaching English at night and I began writing my first novel, "From What Bone," about a young Greek-American, who travels to his father's home village in the Peloponnesus in search of his past (see "A Disturbance of Memory on the Acropolis," Stations One, 1972).

It wasn't until I had returned home to Gloucester three years later that I resumed the study of Dante — ironically after I had decided not to pursue doctoral work in Italian at Berkeley. And that was because under Olson's tutelage I began to look at my own hometown, Gloucester, through Dantean eyes, while discovering the underpinning of the Commedia both in the Cantos and Olson's Maximus Poems.

What has been the influence of Charles Olson on your life and work?

There are certain people in our lives, writers we have read or people we have encountered or known personally, who have, in a sense, given us the world, opened us to ways of looking at the world or understanding our own lives in ways that might never have been possible if we had never met them. Charles Olson was one such person for me, both in terms of our friendship and through his writings.

Olson helped me to understand what it meant for someone like me to have been born and grown up in a singular American place like Gloucester, Massachusetts. He had the ability to peel back the layers of time in a locale, a neighborhood, a single house even, a patch of forest, a moraine landscape, to reveal the depths and dimensions of its history. Olson helped me see that Gloucester was not simply the oldest fishing port in America and, as such, an archetypal place of human activity. He also helped me see that Gloucester was a continually evolving ecosphere, and that an understanding of the rich and complex ecology of my home town and the woods and fields that surrounded it led to an understanding of the natural history, geography and ecology of the larger world.

With respect to writing itself, the most important lesson I learned from Olson was that writers, be they poets or prose writers, should pay attention to what he called "the literal" as against "the literary." By this Olson meant that one need not embellish what one encountered in the world. One need only describe it with exactitude for maximum effect, or as Williams put it, "No ideas but in things."

Olson also encouraged me to study the history of my own town, my region and, indeed, the nation itself, as he had, through the primary documents. Court papers, land transactions in probate, property line surveys, wills and testaments and Quarterly Court records of civil litigation were, for Olson, the ur-texts of history, and as significant as the land itself for reading the passage of human habitation in given places. Maps told him more than narrative histories, though when it came to the narrative he said he found more significance in town histories, written by local historians, than in the dominant works of academic history.

His theory of "saturation," — that you concentrated on one place, one writer, one topic until you had absolutely exhausted it for yourself and therefore prepared yourself henceforth to take on any subject — has proved to be immensely helpful to me in approaching not only the study of individual writers but also of larger topics in literature or history.

Most of all, Olson showed me how to be myself, how to ferret out what lay deep inside me. And he did this by his own example of courage and struggle and by giving me permission to be myself in the way that parents aren't able to do for their children, who often need a mentor to show them the path to further growth and development. Olson modeled the life in art I had always wanted to live. He demonstrated by living in a book-filled $28-dollar-a-month cold-water walkup on Gloucester's waterfront that one did not need to have material wealth in order to pursue the life of the mind. Olson counterposed himself and his ideas against the consumerist culture that was growing around us ("in the midst of plenty/walk/as close to/bare"), noting once, in the pages of the Gloucester Daily Times, "One has to have the strength of a goat, and ultimately smell as bad, to live in the immediate progress of this country."

Finally, it was Olson's activism against Urban Renewal (he called it "Renewal by destruction"), against the loss of Gloucester's historic architecture, against the filling of wetlands and all the "erosions of place," as he called them, that inspired my own activism on behalf of the fishing industry, the preservation of Dogtown Common and against overdevelopment and gentrification. For in the end, my activism and that of those I've worked closely with for over forty years, is about the preservation of place, not only as an idea or ideal but as a real, living, breathing community.

Speak about the roots of your activism.

My activism began with some very conventional community involvement. I was a Junior Rotarian (imagine that!) in high school, which go me into volunteer work, canvassing for charitable causes, helping fishing families who had lost members at sea, and raising money for sports events and art festivals, while meeting a lot of people who, while being quite conservative politically, truly cared for Gloucester as a community and as a place of deep history and remarkable physical beauty.

My first taste of political life began in June 1954 at Boys' State, a week-long summer camp event sponsored annually by the American Legion. Each high school in the state would choose a couple of boys to attend the camp at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. We'd form into towns that elected representatives to an imaginary state legislature. Then we'd elect a governor and state officers, so we'd be replicating the political process, learning how to run for office, how to organize and run a campaign, how to make deals and line up support for our positions. Looking back on that experience, it's now clear to me that it was run by the Legion's right wing political allies, who taught classes in "citizenship" and "American ideals," and ideologically driven by the organization's Cold War agenda. They were trying to indoctrinate us — just boys then, no girls — as young anti-communists (I'm certain I was denied admission to Boys' Nation, the next step up the political ladder from Boys' State, when, during the application interview, I said we should withdraw our forces from Korea). But getting away from Gloucester and spending time on a big university campus was important for me, especially since I discovered a huge book store to roam free in. I remember buying the Modern Library edition of The Philosophy of Schopenhauer, which I still own, and sitting under the trees on the campus during free time reading my very first philosophy. The World as Will and Idea, was my introduction to the philosophy of pessimism in tandem with a formal critique of organized religion and it has continued to be a seminal text for me.

Back in Gloucester, each year we also had a student government day in which high school students literally took the reigns of government, from mayor and city council to health agent, for one day. We'd elect our own mayor, city council and school committee and advance our own student agendas. I participated in this activity for several years, learning a great deal about how local government worked. All this stood me in good stead when I began to confront government years later as an activist.

My first campaign, after I returned home from Europe in 1962, was as part of a group of citizens who were trying to stop the construction of a shopping plaza at the entrance to the city, including a bank branch and a restaurant. Some important people were involved in the campaign, including members of the Cape Ann Historical Association, who wanted to protect what had from colonial times been the town's original village green. We lost, and if you enter Gloucester now from route 128, the first thing you see will be a messy parking lot with a drive-through bank, a Friendly's fast food joint and a Chinese restaurant, not the original welcoming green circled by two of the oldest remaining houses in Gloucester.

A couple of years later I joined a group that worked successfully to raise funds to purchase an area of salt marsh slated for development, also near the entrance to town. Our successful campaign, which we called "Window on the Marsh," brought me into contact with the first environmentally conscious people I'd met. Some of them joined me, in 1967, in a campaign to stop the proposed placement by the Pentagon of a radar base for the Sentinel Anti-Ballistic Missile System on Dogtown Common, the very heart of Cape Ann's wilderness. Just think of such an installation among the terminal moraine boulders that Marsden Hartley had painted and Olson had written about in The Mamimus Poems!

Our campaign was met by furious reaction from many citizens who welcomed a military presence in Gloucester. They called us "Commies," and wrote to the editor of Gloucester Times that if we didn't want missiles to protect us from Russia, we should go and live there. In other words, the whole anti-communist scam. In the end we prevailed and the base was scrapped, along with the entire Sentinel system. But this was at the height of the Vietnam War and I learned how deeply anti-communist, indeed how super- patriotic Gloucester was, a town that hadn't balked at sending its young to die in every war since the Revolution.

I was still in graduate school at Tufts at the time and my wife and I became deeply involved in the anti-war movement, just as we'd previously been involved in civil rights issues (I was seen on Boston TV in 1963, as part of a group of teachers picketing a Hayes Bickford cafeteria in Cambridge that refused to hire Blacks, and it led to my not being rehired as a high school English teacher in Winchester, Massachusetts). I have to admit honestly that I did not at first engage in these activities through my own volition. In fact, I resisted political involvement for a long time. All I wanted to do was write, and I fought any distraction from the writing. But the war was an atrocity. I knew it and I saw my students organizing against it. I supported the ideas and tactics of SDS (Students for a Democratic Society), just as I'd contributed to CORE and SNIC earlier. We attended teach-ins and demonstrations on Boston Common and anti-war marches, so that when I left graduate school in 1967 I was primed for anti-war involvement in Gloucester. This came in the form of an amazing group I soon joined of teachers, writers, artists, poets, young professionals and Old Left activists. We called ourselves Cape Ann Concerned Citizens.

We leafleted against the war, we demonstrated, held petition campaigns and brought well-known anti-war activists like Noam Chomsky, Howard Zinn and Jerome Letvin to Gloucester to speak. At first we received a lot of opposition, but as the war wore on and local kids were killed, as the costs to taxpayers rose, we found many more people on our side to the extent that the Gloucester City Council unanimously passed a resolution we drafted for immediate US withdrawal from Vietnam.

Attending meetings of the group, working with members who had been active since the 1930s in political and social struggles, editing the group's newsletter, Soundings, and writing about political issues in the local paper, provided me with a political education that prepared me for the next thirty years of activism in Gloucester on behalf of the environment, against an appropriate development, for the preservation of the working waterfront and the support of a viable fishing industry.

That was the work on the ground, but there was an important intellectual dimension of my political life that entailed a period of reading and deep study.

Let me go back for a minute to my years in Italy because the roots my activism surely lie there.

In Florence I was in love with a young woman named Rita, who came from the Abruzzi. She was a fiery Communist with coal black hair and riveting eyes, and she was reading political science at the university. We would go out dancing with a group of friends, architects, painters; or we'd sit in the cafes of Piazza della Repubblica or at Rivoire in Piazza Signoria drinking espresso or cappuccino, reading French and Italian newspapers and talking by the hour about the films we'd just seen by Fellini or Antonioni; the American-influenced novels of Cesare Pavese, those extraordinary narratives of post-war alienation, which the intellectual young had such a passion for then, and still do, I'm told. (I first encountered Pavese just after I arrived in Italy and his books swept me off my feet. The story of his life — his imprisonment by Mussolini for anti-fascist activities, his monumental translation into Italian of Moby-Dick, the prize-winning novels and stories he wrote in a pared down, anti-rhetorical Italian, his struggle with and eventual abandonment of Communism, and finally, his suicide in a dingy hotel in downtown Torino — is one the great tragic stories of modern Europe).

It was the time of the Algerian uprising, when the French "paras," who'd been sent in to quell the insurgency, the violent demonstrations, and to frustrate further anti-colonial actions, began to perpetrate unconscionable brutality on the indigenous population. Petitions were being signed all over Europe against the French response to Algeria's natural desire to be independent. There were demonstrations in solidarity with the Algerian people. It was the main topic of the day. Of course, I had no idea what the struggle was about because I had never thought about colonialism. Imagine! My own country had fought a revolution to throw off the shackles of British rule and I couldn't make the connection. I even defended the presence of America bases in Germany and Italy!

One day Rita and I were alone. We'd taken a walk along the Arno after classes and were sitting in a café near Piazza Beccaria, sipping Punt e Mes under a warm spring sun. The night before we'd been to see Il bell' Antonio, with Marcello Mastroianni and Claudia Cardinale. Based on a novel by Vitaliano Brancati, the film is about a young upper class Sicilian, who makes love easily with working class girls but becomes impotent with women of his own circle. After some strained talk about the film, during which Rita tried to help me see how Antonio's dilemma was a metaphor for class struggle in Italy, she turned to me. By then we'd only kissed on park benches, or fondled each other fleetingly on the couch in my room in Via dei Servi, always attentive to the presence of my landlady on the other side of the wall.

"I like you, Pietro," Rita said. "And I enjoy spending time together. But you remind me of myself when I was in liceo. We're miles apart politically, and you're still very young emotionally."

The Italian students I met were quite mature; and they were very serious, serious about their studies and serious about politics, about the world. I was serious about literature, about things intellectual, but in retrospect it's clear to me that I didn't know how to be in a mature relationship. And I was in kindergarten politically. I'd never really thought through the myths we were conditioned to accept in school and college; you know, that the United States is the great bearer of democracy, that our intentions toward the world are always honorable, that we are committed to protecting the weak. Though they were grateful to us for our war efforts and for the Marshall Plan that followed, Europeans remained skeptical about our intentions. My Italian friends used to say: "Never mind American rhetoric, just look at your government's behavior!" And when I heard stories about OSS agents with suitcases full of dollar bills buying votes for the Christian Democrats after the war, when it looked as if the Italian Communist Party might actually come to power, the scales began to fall from my eyes, though they didn't fall completely until Vietnam, which was the turning point, as I've said.

After the horror — the obscenity of our actions in Vietnam, the secret wars we waged in Laos and Cambodia, the napalm, the burning of villages, the massacre at My Lai of women and children by American soldiers, the lies about the body counts and about our reasons for intervening — I never felt the same about my government again or about America. You can imagine how I feel now with the country engaged in yet another illegal and unnecessary war, two of them in fact, fought by working class kids, Latinos and Blacks; a war which we lied our way into and which has turned the rest of the world against us. Talk about déjà vu.

In any event, Rita broke up with me. We saw each other from time to time, but it was clear she'd drawn a line. Then I stopped going to class so I could have more time to write. I was teaching at night, so I wanted the day time for writing. I also wanted time for travel and for exploring the vast treasure house of Florentine art. But the fact of the matter was that I needed to grow up. I needed to grow up emotionally and I needed to come to some mature understanding of political life, especially if I wanted to write.

Arriving at such an understanding took several more years, until I was smack in the middle of the antiwar movement as a graduate student, when my wife and I began attending demonstrations, as I've said, and going to teach-ins, really at her urging because she was far more politically engaged than I was. That's when I started reading the major political and social texts of the 19th and 20th century, Marx, Engels, Bakunin, Kropotkin, Lenin, Trotsky, Edmund Wilson's To the Finland Station, C. Wright Mills' critiques of American capitalism, and of course all of Herbert Marcuse's books. For years I hardly touched contemporary fiction or poetry. All I read was history and politics. I had to teach myself everything I hadn't learned about the world as a liberal arts student during the Cold War — everything that had been withheld from me by my teachers.

It was the most profound education of my life, this reading of Thorstein Veblen and Randolf Bourne, of Georges Sorel, of Gunnar Myrdal's An American Dilemma, Adorno's The Authoritarian Personality, Ray Ginger's masterful biography of Eugene Debbs. I immersed myself in everything from Schlesinger on FDR to Deutscher on Trotsky. I scoured the major books on the Russian Revolution, from John Reed's Ten Days that Shook the World to Adam Ulam's The Bolsheviks. I read Henry Adams on the degradation of democratic dogma and Julian Benda on the betrayal of intellectuals. I read Bertrand de Jouvanel and Ronald Sampson on the nature and psychology of power, Elias Canetti on crowds and power, and Hannah Arendt on totalitarianism. Then I turned to Gramsci's Prison Notebooks. I even read Erich Hoffer's The True Believer. I wanted to explore all sides, take in all views, though what drew me principally were the texts on the Left. I read most of the major American proletarian novels along with Rideout's The Radical Novel in the United States and Daniel Aaron's comprehensive Writers on the Left. I studied the Sacco and Vanzetti case, and I read the Lynds' book on Middletown along with David Riesman's The Lonely Crowd. I also read the writers and analysts of the day — Howard Zinn, Noam Chomsky, and their predecessors, Dwight Macdonald and the Partisan Review and New Masses editors and writers. Then I read Frantz Fanon on racism and colonialist psychology, followed by the Autobiography of Malcolm X. I must also mention Guy Debord's Society of the Spectacle and many of the other writings of the Situationist International, which have continued to influence my view of the world, providing me with an analysis, which I still find incredibly today, indeed incredible prescient.

I emerged in the 1970s as a very different person, and, I believe, a more thoughtful one, though not an ideologue. Ideology of any stripe is anathema to me. I'm as suspicious of its temptations — and its excesses — as I am of religion's. I no longer viewed the world through purely literary eyes, no longer trusted anything on its face. I'd finally become a skeptic, which is what my teachers at Bowdoin had always exhorted us to become. But most of all, I came away from my reading in history and politics with a profoundly tragic view of life. What I'd only understood intellectually from studying Shakespeare and the Greeks, that life is essentially transitory in nature and human beings seem doomed to repeat their mistakes, I now experienced viscerally. I'd become a pessimist. It's difficult for me not to believe that human beings seem hell bent on destroying our species or the planet that sustains us, and I have little hope for any change in the trend.

What about your activism after the war in Vietnam?

As the war in Vietnam ended, the members of the Cape Ann Concerned Citizens broadened their interests to include issues of ecology and conservation. Some participated in the New Hampshire Clamshell Alliance that was battling the development of a nuclear power plant in Seabrook. I joined a group which opposed the building of an access road across the Babson watershed in order to gain entry to a proposed industrial park (I always thought the name "industrial park" to be a contradiction in terms). The Fishermen's Wives, a group of wives of local fishermen who had become politically active, also opposed it because, they argued, any threat to the city's water supply would be a threat to the fish processing industry. Proposals for high-end subdivisions and luxury condominiums began to surface as Gloucester was slowly targeted as an "undeveloped" community. Neighborhood groups quickly organized to fight these proposals, many of which were fortunately denied at the permitting level, though there continued to be protracted battles. Natives prized the precious open spaces of Cape Ann and we loved the vistas everyone enjoyed of the waterfront and the ocean. Though we understood that there would clearly be development pressures, as Cape Cod and the southern coast of Maine succumbed to the drive for vacation homes and condominium lifestyles, we also argued that the people of Gloucester should be the primary determiners of their own fate, deciding together which kind of development we needed and where it would be located. A Master Plan was created, with important community input, a process which helped citizens to appreciate the value of open space, productive wetlands, and unimpeded views of the ocean. Though updated at ten year intervals, the plan was infrequently adhered to in the rush to develop that grew in the 1980s and 90s.

It's a struggle that continues today, as the city council recently caved in to a proposal for a complex containing a shopping mall, a commercial hotel and an assisted living facility, which those residents who most need it won't be able to afford — a proposal for which the developer requested and received a nearly three-million dollar infrastructure subsidy from the city's taxpayers at a time of severe fiscal constraint. A leading resort consortium has expressed interest in developing a hotel at the Fort neighborhood in downtown Gloucester, once the heart of the city's fishing industry, and there are several proposals in the pipeline for high-end retirement housing, which would create new gated communities and fill even more open space [fortunately the current economic situation has either slowed down or will kill these proposals]. Over the years, many local politicians fell for the entreaties of developers, who argued that condominiums and subdivisions would expand the city's tax base, especially as the fishing industry experienced a series of downturns due to fluctuating stocks and over-fishing by Russian factory trawlers before the 200 mile limit was set. But neighbors whose own privacy would have been undermined by dense housing development fought back, defeating a number of controversial housing proposals, one of which called for an 18-hole golf course in the West Gloucester woods, while another sought to build condominiums directly on Gloucester harbor. It was a contentious time in the community, beginning in 1985 with a campaign ultimately to last for a decade against an initiative to construct a 24-store shopping mall with two restaurants and an underground parking garage on the last undeveloped waterfront parcel in downtown Gloucester.

The proposed mall was to be called Gloucester Landing and it met with immediate opposition. "It just isn't Gloucester," many natives protested, including members of the city council. Five thousand residents signed a petition against the project and over four hundred attended a public hearing to demonstrate their opposition to the mall. But there was money and power behind the proposed mall (we were later to discover that our liberal Democratic state representative lobbied for it, along with Governor Michael Dukakis — and a former Lt. Governor was the project's legislative and environmental consultant). The proposal passed the city council by a single vote, from a councilor, who had previously opposed the mall but had strong ties to the Democratic proponents and political ambitions of his own. Due largely to the efforts of Damon Cummings, a Gloucester native, MIT professor, and naval architect, the permits for the mall were appealed at all levels, resulting in the denial of a license for the project by the state coastal zone management agency that regulates use of Commonwealth Tidelands, under Chapter 91.

The anti-mall fight drew from the community a remarkable range of participants. Beginning with the fight against Gloucester Landing, Lena Novello and Angela Sanfillippo, president and vice-president respectively of the Gloucester Fishermen's Wives, became powerful adversaries of any attempt to undermine the working waterfront. They were joined by Margaret "Peggy" Sibley, who had arrived in Gloucester as an English war bride, married to fishing Captain Bill Sibley. Peg, as we called her, brought a fierce intelligence and a powerful ability for persuasion to the struggle to preserve Gloucester's watershed and our maritime way of life. Joining Peg, Lena and Angela was Carolyn O' Connor, a strong environmentalist and advocate for the preservation of local character and an officer in the Gloucester Civic and Garden Council. Carolyn had been a city councilor whose foresight helped to save the Babson Watershed, named after economist and native son, Roger Babson (Babson had given this land to the city, along with considerable acreage in Dogtown Common, which abutted the watershed). Together, they helped form a flexible cohort of local activists, who could be counted on to organize the members of their respective groups whenever a controversial development scheme surfaced; and there were many, coming one on top of another, as developers seemed to salivate over the open spaces and oceanside properties that remained here.

Following the battle against the mall, in 1985-86, some waterfront owners pushed to revise the zoning ordinances along the working waterfront to include non-marine uses such as commercial space and housing. Another struggle ensued, this time with the Chamber of Commerce on the side of those who opposed the changes. Fortunately, in this instance the council, led by former fisherman John "Gus" Foote, rejected the proposed zoning and Gloucester's waterfront remained protected against the incursion of condos, as the Portland waterfront had not until it seemed too late.

During this time — from 1978 until 1990 — I had been writing a weekly column for the Gloucester Daily Times at the urging of editor Peter Watson, who wanted more community presence on the editorial page. Given carte blanche by Peter, I began to address local issues, using my column to advocate for more comprehensive planning and for a greater understanding of the beauty and value of Gloucester's landforms, our pristine forests, and our social ecology, including the variety of ethnic neighborhoods the community boasted. I advocated for the preservation of neighborhood schools, when the school department moved to close them, consolidating the system into overcrowded magnet schools that soon became unmanageable. Along with teachers and some city councilors, most of us products of neighborhood schools, I argued that the closing of these small but vital facilities would create a social and educational vacuum in the affected neighborhoods. The schools were eventually closed over the overwhelming protests of teachers and parents. A dozen years later the school department admitted that the closings had been a mistake. But by then the classic red brick school buildings had been sold or put to other uses and the city's education system had already suffered from their loss.

I wrote in my column about growing up in Gloucester and about being a parent. I wrote about my job at Action, about poverty and homelessness, which was on the increase in the 1980s. I also wrote about local, state and national affairs, offering close analysis and criticism of what I believed were the incredibly regressive policies of the Reagan administration. Those columns opened up a dialogue between me and my hometown, a dialogue I had never before enjoyed. People stopped me in the post office to praise or disagree with what I'd written the night before. They wrote rejoinders in letters to the editor or in guest columns, as the Gloucester Times opened its editorial pages to the entire community, winning many prizes in the process and increasing its loyal, if often fractious, readership.

Suddenly I had become a public writer, someone people read and responded to. Many had never read a word by me, since most of my writings, except for Glooskap's Children and the oral history Peter Parsons and I prepared, had previously appeared in little known or underground publications. Considering the stinging remark that had been confided to me when we first moved to Vine Street — one of our new neighbors asked another what I did for a living and received the reply: "Nothing. He's a writer." — I realized that for better or worse everyone who now read the paper knew what I did, whether they agreed with my opinions or not.

Gradually my life in Gloucester changed, as I opened myself to the challenges offered by advocacy work at Action, writing a weekly column in the paper, political activism and public service, and teaching. The identity crisis that I was clearly suffering from after I returned to Gloucester and during my marriage, accompanied by a crisis of vocation, was reaching resolution, particularly with the help of my job at Action.

How did you become involved in social work?