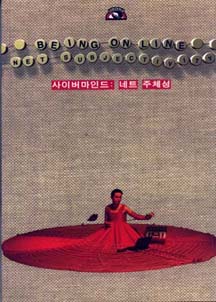

| Being On Line, Net Subjectivity  |

Net romances often follow a

course of "increased embodiment," from personal email to one

of the chat applications in private mode, and from there to telephone call,

exchange of letters and photographs, perhaps exchange of video and real

hair, etc. - the exchanges becoming increasingly eroticized as well, until

there might be an "f2f" (face to face) or "fleshmeet"

at the end. The very fact that these uncomfortable terms have arisen indicates

the appearance of foreclosure and autonomy in cyberspace - "within"

it, it seems to possess its own being...

From Introduction to

Space, by Alan Sondheim |

|

From "lol," a post by Alan Sondheim Lusitania Press is pleased to announce the publication of Being On Line, Net Subjectivity. This anthology addresses the exciting new consciousness of the Internet, where identity is negotiated and love is the pleasure of the text. The contents range from sexually intense analyses of on-line writing to the "netwar" of the Zapatistas. Edited by Alan Sondheim, Being On Line, Net Subjectivity is conceived as an exploration of the theory and practice of virtual identity as well as its effects. Unlike many recent books on the Internet, Being On Line focuses both on the promises of the technology and the actual content being developed by users of this form of exchange. Intermixed with the esoteric ("Monogamousbody") and the cybernetic ("Are you a Cyborg?"), are topics ranging from subjectivity and community to the uncanny and netsex, presented in both theory and practice. Among the thirty-two authors are Angela Hunter, Ellen Zweig, and Nesta Stubbs; net feminist Doctress Neutopia; anthropologist Roger Bartra; and theorists Friedrich Kittler, Slavoj Zizek, Mark Poster and Gregory Ulmer. Being on Line is richly illustrated by artists whose works are related to virtual worlds. Four color sections present performance, graphics and sculpture by Regina Frank, Peter Halley, Mike Metz, and Alice Aycock. Being On Line includes Lusitania signature "editorial" in comic strip format. Being on Line, Net Subjectivity is 208 pages, with 16

pages of color and 192 illustrated pages in black and white. In English

and Korean. Being On Line, Net Subjectivity can be ordered from D.A.P/ Distributed Art Publishers, 155 Sixth Avenue, 2nd Floor, New York, N.Y. 10013-1507 or call toll-free 1-800-338-BOOK Excerpt from the Introduction

The art is somewhat different. There's lots of computer art, but I wanted to include work that reflects the spaces and even "psyches" of the Net, instead of technology. So many of the pieces have no direct relationship to computers, but they all reflect on cyberspace, avatars, the uncanny and the imaginary. The spaces between the artworks and texts are inhabited as well. This last is critical. If I join an email list, and don't say anything, I'm a "lurker" The odd connotations of the word aside, I basically have no presence, no existence on the list for others, until I post something, the post is both about something (ostensible content) and a statement of existence. When I cease posting (or cease, say, speaking in a MOO), I'm no longer there, or might be there as a presence if a "who" command is given, but nothing more. So speaking/writing on the Net is equivalent to existing for others; silence is absence. Another point concerns what I call "hysteric embodiment." There is great deal of writing about cross-gender on the Net, that females may pass as males, and vice versa. When we read a post or reply, then, we're given three layers of information - the ostensible content of the writing, the passing references to the writer hirself (which we use to begin to construct an image), and sub-textual information which results in projecting an image of the other, with the post as symptom. This last, hysteric embodiment, references the theory of hysteria in which trauma locates itself in part of the body; on the Internet, the body locates itself by the act of writing, in writing itself. This form of writing, which embodies a projected body, I call wryting, since it is performative, producing its own author. In other words, there's an odd inversion at work. On a naive level in real life, one begins with the real, which relates to signifieds coupled with signifiers related by difference among each other. There are real trees, there are imaged trees, and signifiers which represent them; the signifier of the imaged oak is different from the imaged palm, and the differences form a semantic field. (Sorry for the reduction here.) On the Net, it's the opposite. One begins with the text of the other, which is directly coupled only to text and exchange of texts - and out of this, one constructs a real, constructs a world which is projected onto the other. Sometimes as in a MOO, the entire environment is a textual projection, as in a novel (and in this light, an email list becomes an epistolary novel); more often than not, the projection occurs in relation to wryting among participants in any application. The difference between this sort of projection and that which occurs in a novel, may be nothing more than intensity and investment. In email exchanges, one assumes (not always correctly) that the partner is human, and engaged with one; it's this that operates in the search for a kind of truth which always remains elusive. Net romances as a result often follow a course of "increased embodiment," from personal email to one of the chat applications in private mode, and from there to telephone call, exchange of letters and photographs, perhaps exchange of video and real hair, etc., - the exchanges becoming increasingly eroticized as well, until there might be an "f2f" (face to face) or "fleshmeet" at the end. The very fact that these uncomfortable terms have arisen indicates the appearance of foreclosure and autonomy in cyberspace - "within" it, it seems to possess its own being, something described quite well, for example, in Sherry Turkle's Life on the Screen. Finally, there are issues of net sexuality and pain to consider; these play a role in this book. I've found net.sex to be extremely powerful, almost as much as "f2f." Net.sex in text mode plays into an "ascii unconscious," the mutual spelling out of desires, commands, and positions; the fantasies that usually accompany any sex suddenly appear "real" and generated between you and your partner/s. What was implicit becomes explicit; what was thwarted becomes liberating. The result can be overwhelming. And pain, to the limit of death and mourning, always plays a role here. I first experienced the "power" of cyberspace when the co-founder of Cybermind, Michael Current died. I sent out a short eulogy on the Net, and received, without warning, a great number of email posts and even telephone calls in response. The Net permits both pain and empathy, and some of the voices in Being On Line speak eloquently to that. But enough. You can always go to my URL for hundreds of pages of meditation on cyberspace. I want here only to dedicate this volume to two people who have made it possible - Clara Hiela, and Michael Current; the text of his I have included arrived in my Inbox the day before he died.

| |