|

|

IT IS ENOUGH FOR ME

MÁRTON KOPPÁNY & POETRY'S REWARD

By Peter O'Leary

Bácskai ut. 22,

The Institute of Broken and Reduced Languages

In Herminamezo, the heart of old Zugló, Budapest's leafy Fourteenth District, itself part of the green belt of the Pest that separates the treeless, slowly-gentrifying, nonetheless-still-crumbling-and-sooted warrens of the 19th century downtown from the sprawling Marxist apartment-block suburbs and the abundant fields of Hungarian grain beyond them, live poet Márton Koppány and his wife Gyöngyi Boldog, a university teacher, with their garrulous dog, Gertrude Stein. Their flat is on the third floor of a pleasant building, surrounded by trees and clusters of bushes, as well as the incessant sounds of nearby construction, a seemingly interminable sign of Budapest's improving position in the new European Union. It's a modest flat, lovingly kept, with four rooms, lined from ceiling to floor with books and art-objects, through which, in the springtime at least, a soft light filters.

[Márton, Gertrude, and Gabriel, June 2003]

They have lived here for eighteen years. It's immediately felt as an inhabited space, humanized, marked with signs of life, the lingering smell of onions frying, say. Among the paintings, photographs, and poems framed and hung on the wall, one finds taped above the main light switch in the living room a piece of paper on which Aram Saroyan's legendary concrete poem is printed: "lighght". The first few times I visited this apartment, I always pointed to it, laughing, and Márton would laugh too. It's funny, after all. But its placement is also deeply imprinted with Márton's poetic care, and with the impish way he goads poetry into his world. Saroyan's poem on the page is an illuminated zen koan of language; a wry, ironic, incisive demonstration of the powers of language, such that the silently passed-over "gh" demands somehow to be mentioned, even in its unsounded silence. The reading eye sees and then hears it. On the level of this readerly conundrum Saroyan's poem has mainly lived, as a simultaneous moment of clarity and confusion. Márton's placement of this poem in his physical world, however, ritualizes the poem, transforming the expression of that extra "gh" into physical presence. The sound of the silent "gh" is commemorated whenever the lightswitch is flipped. Kafka, in one of his briefer parables, wrote:

Leopards break into the temple and drink the sacrificial chalices dry; this occurs repeatedly, again and again: finally it can be reckoned on beforehand and becomes part of the ceremony.[1]

Márton's placement of Saroyan's poem is a fore-reckoning, then, of a ritual repeated again and again, making a little poetic ceremony of turning the light on and off.

Márton and I met at Woodland Pattern Book Center in Milwaukee in 1996. We arranged to meet after Márton had sent some of his work to LVNG, the literary magazine I co-edit. My fellow editors and I were fascinated and decided to publish some of it—one piece in LVNG 7, another as a number in the LVNG Supplemental Series. When we met I saw an unassuming man, with reddish-gray hair, a trimmed beard, whose face is defined by his hypermetropia — farsightedness — for which he wears glasses that cause his eyes to appear hugely magnified, giving them a sad, bemused cast, so that expanded in the disks of his eyeglasses, they lend to him something of an aspect of a saint, beatified. As we chatted in the bookstore, looking through its vast poetry section, I asked Márton how he liked living in Milwaukee. (Gyöngyi was at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee for the year doing graduate work in Linguistics.) He told me he loved it, adding, "It's much safer than Budapest." I pulled my eyes from the bookshelves, looked at him and said, a bit surprised, "Oh, I didn't realize that Budapest was a dangerous place." There was a pause. Another pause. Another. Haltingly, he explained, "Well, existentially speaking." It took me a few seconds to realize that this was a joke. It has taken me a few years longer, however, to realize it is not. There is a feature of Márton's work and thought that is central to its value for me, its simultaneous humor and seriousness existing on an almost holographic scale: if you hold it at one angle, you see how philosophically morbid it is but hold it at another and it seems to be a joke. The mystery and potency of his work, however, exists in a third perspective, arrived at through an act of patient contemplation. Karl Young has noted of Márton's work, in comparing it to the work of bpNichol, that it attains its depth through its playfulness. "The poetry of both," writes Young, "seems to me examples of strong individuals' abilities to deal with the darkness of existence without being sucked into it and without projecting it." [2]

Márton's work is most obviously characterized by the dry humor at work in it. His poem, "It is the Same," (which we published as a LVNG Supplemental, begins as a notecard divided down the middle by a black line. In the center of both white fields of the card appears the phrase "it is the same," with the number 1 in the bottom right corner of the field. The next card appears the same, but with a different phrase — "he makes the traces disappear" — and a number 2 in the corner. The third card repeats the first, with "it is the same," but this time the number 3 in the corner. The fourth card blots out the whole right side in black. On the left side, it reads, "it has disappeared," with the number 4 in the bottom corner. The fifth card completes the sequence, this time with the left side of the card blotted black, so that the right side reads, "it has disappeared," again with the number 4 in the bottom corner.

The humor of this poem arises out of the absurdity of watching the poem demonstrate what it is doing, so that the poem is both a joke and a commentary on that joke. Márton feeds off the absurd in his work, lending it an air of the surreal. In some ways, this might be enough of an orientation to appreciate Márton's work and enjoy it, but we would be missing out on its more contemplative, metaphysical dimensions. In order to perceive these dimensions, we can observe the seemingly neutral irony that Márton employs toward a meticulous undermining of his work. In The Concept of Irony, Kierkegaard, in looking for "the total concept of what irony is," argues that "irony is a qualification of subjectivity," and that the "ironic figure of speech cancels itself . . . . inasmuch as the one who is speaking assumes that his hearers understand him, and thus, through a negation of the immediate phenomenon, the essence becomes identical with the phenomenon."[3] This is a somewhat complex way — in a very complex and nuanced argument I cannot do justice to here — of saying that irony is language that empties itself of meaning, replacing that subject with itself, and that this very act qualifies subjectivity through a kind of self-consciousness.

Throughout The Concept of Irony, Kierkegaard is somewhat critical of irony's rhetoric, focusing much of his criticism on the nature of Socrates' irony. For Kierkegaard, Socrates exemplifies the ironic position, in all of his incarnations — including those of Xenophon, Aristophanes, and especially Plato. Following an example of Socrates' reliance on his daimon (which Kierkegaard sees as a replacement of the oracle), Kierkegaard writes, "Here again Socrates proves to be one who is ready to leap into something but never in the relevant moment does leap into this next thing but leaps aside and back into himself" (166). In emptying something of meaning in the employment of irony, Socrates invariably replaces that emptiness with himself. Irony, for Kierkegaard, is only redeemed when it is replaces with a fullness rather than an emptiness. Kierkegaard's example for this is Christ's crucifixion — the ironic gesture of dying in order to save the souls of humankind, which have been emptied by sin is replaced by the potent presence of Christ himself as savior, filling the emptiness with salvation itself.

Now, this is perhaps a scale of irony inappropriate for reading Márton's seemingly slight, and usually witty poems. Nonetheless, I think Kierkegaard's concept of irony allows us to perceive the underside of Márton's transparent humor, in hopes of finding not an emptiness of the absurd underlying his work, but a meaningful, if mysteriously forlorn and hopeful, expression of the powers of poetry to redeem language of its meaninglessness.

Partially to consolidate some of his various publishing efforts — his own poetry and the work he was editing at the time for Kalligram, a Hungarian press based in Bratislava — but more importantly to articulate a program or philosophy by which he would understand his work, Márton conceived of and has furthered the mission of the Institute of Broken and Reduced Languages seven years ago. Frustrated by labels such as visual poetry, minimalist poetry, or conceptual art, Márton began to conceive of his work as a process of breaking and reduction. (I will elaborate this process later in the essay; for now, we can understand this to mean, partially, a breaking away from Hungarian to English, and a reduction of poetic intentions to a minimum of words.) There's characteristic humor in the institute's name as well, in Márton's sense that the English in which he was composing these works is broken, at best. "What remains," he asks, "if I abstract away from the anecdotal and psychological details of my personal history? Certainty of Death and Certainty of Nothing at All are playing ping-pong in the final of an elimination tournament."[4] To this humor, I would add an additional pun on "broken," namely, that Márton's poetry appears in a condition of brokenness, one that is as psychological as it is historical. It's impossible, once we know his story, to which I will presently turn, not to read something of it into his poetry, not so much to reinforce notions of identity poetics and how they affect creative production, but to propose that the person making these works — and the decisions that inform them — is, like Kafka's alter-ego, endlessly "before the law" of himself and his life.

Before looking into that life, consider the poem, "I'll Regret It," as an instance of breaking and reducing language, shaping it equally with morbid humor and ironic revelation.

We published "I'll Regret It" in LVNG 7. It is one of my favorite of Márton's poems, one of my favorite poems of all. The joke of the poem is transparent: yes, that's right, you'll surely regret it, having torn the page of the poem. But is its stance transparent, too? We're entrapped in a murky existential moment in this poem, one in which the darkness is surrounding us. Deeds or decisions are as much regrets as they are acts. (To make a decision is to choose not to do something else, something perhaps more desirable.) This is especially true in the commitment of a poem to paper. What is this sad thing doing here? By breaking/tearing the utterance of the poem — quite literally/visually down the center — and by reducing the occasion of the poem to two simple cards, a repetitive gesture, Márton makes it both its past and its future: endlessly, and now ritually, recycled in the imagination.

Going to the Other Side

The force of evil is often referred to by the Zohar as sitra ahara, the "other side," indicating that it represents a parallel emanation to that of the sefirot. But the origin of that demonic reality that both parallels and mocks the divine is not in some "other" distant force. The demonic is born of an imbalance within the divine, flowing ultimately from the same source as all else, the single source of being.

—Arthur Green, A Guide to the Zohar

In the Spring, 2004, I lived in Budapest for two months; while there, I decided to make one of my projects a series of interviews with Márton with the idea of writing this essay on him and his work. We arranged to meet once a week for this purpose. (We met frequently, and happily, for other, non-literary purposes.) Typically, we would go to a café or a restaurant; as the spring began to bloom, we found a very pleasant outdoor café in an old park near Hungary's Parliament building, an oversized, Neo-Gothic splendor, somewhat absurdly the largest parliamentary building in Europe, in the fifth district of the Pest. We would sit there in the evenings, sipping coffee or mineral water.[5] Sometimes we would take extensive walks through two of Budapest's parks — the lovely Városliget, or City Park, which is quite close to Márton's apartment, or the Margit-sziget, or St. Margaret's Island, which is a park not far from the apartment my family and I were renting that spring. The Margit-sziget lies in the center of the Danube, whose flow it cleaves. In its center you find the ruins of the Dominican monastery where the island's namesake, St. Margaret, lived in the thirteenth century.

[Margit-sziget, April 2004]

One especially memorable interview took place in the middle of April, during a steady drizzle, while we strolled under the canopy of emerald-budding trees on the Margit-sziget, and Márton offered to me a history of modern, twentieth-century poetry in Hungarian, connected throughout by his thorough, and even reverent understanding of this literature. Márton, in trying to make me appreciate the relationship between poetry and the Hungarian language, which is readily appreciated by its speakers to be the most poetic language on earth, explained that Hungarians thought of themselves as intrinsically poetic every time they speak. This prompted me to quip something about a nation of nothing but poets, thinking of the Olson adage. He said, deadpan, "I can't think of anything more unappealing." Somehow, this prompted me to suggest a nation of nothing but sausage-makers, to which Márton responded, this time more perkily, "There must be at least one or two good poets among sausage-makers. It's human nature."

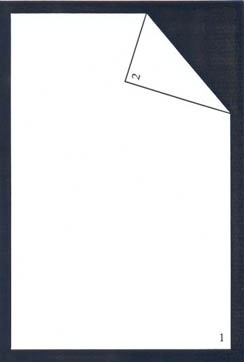

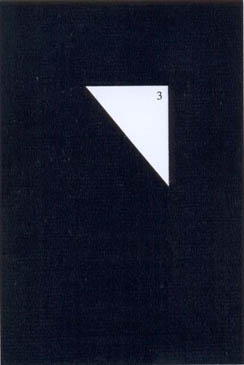

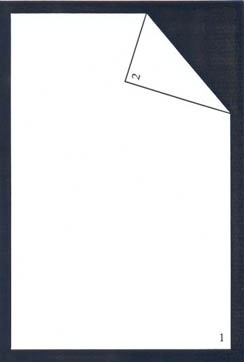

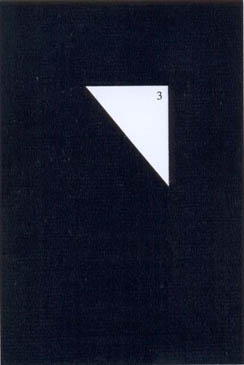

One of the first poems of Márton's that I read was his postcard piece, "The Other Side." It's the title of a short collection of the postcard poems, all of which are characterized by the thick black border that surrounds his texts. The poem appears as a visual joke, in which a card has its upper-right corner folded over, revealing black space/blank space on the other side. On the first page of this poem, the number "1" appears in the bottom-right corner and the number "2" on the folded-over corner. The second page of the poem supplies the joke: a triangle — identical in shape to the folded-over corner — floats in a pitch-black space. There's a number "3" printed in one of the corners.

It seems whenever we would get together, or prepare to get together, mention would be made by Márton or me about the "other side," a common-enough phrase made more geographically useful in Budapest, where the city is in actuality divided into sides by the Danube.

But the "other side" served as well as a thematic location for our conversations, replete with mythic overtones, where we talked about Márton's work, since we spoke always in English, the language he had adopted for writing his poems. Each time we talked, we crossed over to the "other side" of language, crossing a cultural and linguistic divide. Márton's rejection of Hungarian poetry and literature — by which I mean his decision no longer to write in his native language, in favor of patently less poetic English — is an expression, I think, of his feeling of being exiled in his own language. Writing in English, and explaining the glories of Hungarian poetry — he pointed especially to the work of János Pilinszky, Sándor Weöres, and Dezso Tandori, each of whose writing has exerted a powerful influence on Márton's own work (Márton carried on a correspondence with Tandori for a few of years, for instance) — Márton was tracing for me the essential spiritual imbalance he addresses in his poetry that he felt he could no longer accomplish by writing in Hungarian. For Márton, the other side of Hungarian is American English.

Furthermore, the projective space of the "other side" oriented the spiritual and mystical concerns we share in our understandings of poetry. When I explained to Márton in the summer of 2003, while we were visiting Budapest to lay the groundwork for our 2004 stay, that I was working on a project about reading and writing religious poetry, he laughed, asking, "How is it possible to determine what is religious poetry? All poetry is essentially religious." I took him to mean that the act of committing a poem to paper — or any equivalent medium — is an act of faith, thus fundamentally sacral. For Márton, each poem forces the poet and reader to cross to this mythic but necessary other side, at once alienating, ironized, but also, in its heart, transformative.

In our conversations, the "other side" — supercharged with meaning in the manner of one of the lines of an I-Ching hexagram — had the valence to switch suddenly into the other "other side," a kind of transparent, alienated, but cared-for version of whatever side of our discussion we would find ourselves on: by simply invoking this phrase, Márton or I could invert our sense of place, providing a sudden awareness of what we were doing that acted like a cold splash of water. The "other side" was always right underneath our feet. In some senses the "other side" represented the other side of Márton's irony: he uses irony not for self-aggrandizement or to exhibit his superiority; rather, he uses it to undercut his presumptions about reality. When Kierkegaard writes of irony that it "is a position that continually cancels itself; it is a nothing that devours everything, and a something one can never grab hold of, something that is an is not at the same time, but something that at rock bottom is comic," he is providing a way for us to understand Márton's sense of the other side. Whatever he deems real, there is an other side to that reality, one as lucid and surprising as a triangle suspended in the darkest depths of the page. The mind. Poetry itself.

The Poet of the King's Way

"Never will you draw the water out of the depths of this well."

"What water? What well?"

"Who is it asking?"

Silence.

"What silence?"

—Franz Kafka, A Fragment

Márton was born in Budapest. His father, another native of Budapest, whose father was born in Transylvania, was a furrier; he passed away in 2004. His store was on Király utca — King Street, a narrow, aging street that divides the seventh from the sixth district, two of the oldest in Pest. For the first ten years of his life, Márton lived in a flat above this store. This is in the heart of the oldest part of the Pest, the Jewish quarter of town, around the corner from the Great Synagogue. [6] Walking across Király utca one afternoon, remarking on the somewhat dilapidated condition of the street, Márton said that if you go into a European capital, you will always find a King Street. It will be the oldest street in the city, and will typically run through the Jewish part of town. [7] The Koppány family — needless to say? — is Jewish. [8]

When he was ten, Márton's family moved into the Madách-buildings, a vast, brown-brick apartment complex built between the wars close to one of the hubs of the Pest, Vörösmarty tér, which rests at the edge of present-day pedestrian area leading toward the banks of the Danube, lined today with shops, restaurants, and cafés. Márton described this to me as a good place to grow up, because his family had a lot of space in its apartment, relatively speaking, and they were still close to where his father worked.

Koppány — the family name — is as idiomatically Hungarian as O'Leary is Irish, instantly, recognizably so. Márton's father — who was born László Kornhauser — changed the name after Márton, his only child, was born in 1953. His father's family did not fare well in the war: his father's father died — Márton was named after him — and his father was liberated from the Mauthausen workcamp at the end of the war by the U.S. Army. When Márton was born, his father felt that it would be easier perhaps for him to make his way in life with a name not so obviously Jewish. In the summer of 2003, Márton told me a memorable story related to his name. As a young poet, he had some work accepted by Élet és Irodalom ("Life and Literature") a very good weekly, according to Márton, which still exists. One of his poems was published there as early as the late 1970s. In 1983 or '84, Márton had a prose piece accepted, one in which he describes how the dead ought to behave in a cemetery. The editor, when he met Márton, upon seeing him said, "I thought that you were a high school teacher of Hungarian literature in a small town." The implication was immediately obvious to Márton: he was thinking, "So, you're a Jew just like me," something he would never have said aloud. Márton remembers the editor saying this with more irony than arrogance or disappointment. But the story is instructive nonetheless about what it means to be both a Jew and a writer in Central Europe. I'm reminded of a story about Robert Duncan, whose Theosophist grandmother upon hearing him declare that he intended to be a poet, chirped, "But Robert, that's what you were in your past life."

Márton's mother, born Lia Englander, is from Zemun (Zimony in Hungarian), an area that belonged to Yugoslavia during the two wars,[9] the daughter of educated Jews. In 1941, when the German (and Hungarian) troops invaded the country, her grandparents succeeded in sending her, in the very last moment, to Budapest — with the help of forged papers. (Her own mother had died when she was three years old, and she was raised by her grandfather, a nephew of Theodor Herzl, the founder of Zionism, and her grandmother). She was thirteen when she escaped, the only member of her immediate family to survive the war. (The father, grandparents, and two uncles died.) She married László Kornhauser in 1949 and in 1953 gave birth to Márton. I asked Márton about his mother's language, since she had grown up speaking German at home, and Serbian at school, but has lived most of her life in Budapest. He said to me, with obvious pride and affection, "Her Hungarian is perfect." (She retains her German but has lost her Serbian.) While he was growing up, his mother transferred her interest in literature to her son, doting on him with new classics, such as Thomas Mann, Heinrich Mann, Stefan Zweig, Franz Werfel, and Lion Feuchtwanger. Márton's schooling allowed generously for reading: his school days alternated every week between morning and afternoon sessions. So, for one week, he would attend school in the morning; another week, he would attend school in the afternoon. On the days he went to school in the afternoon, his mother let him to sleep in, bringing him breakfast on a tray, so that he was allowed to linger in his bedroom and read to his heart's content. He recalled this experience as "like in a dream, lasting the whole elementary school period." In communist Hungary, book publication was subsidized by the government. And because Hungarian represents such a small language group, there is a great deal of energy put in to translating works from other languages into Hungarian. In Márton and Gyöngyi's apartment, for instance, there are editions of nearly all of the great works of European literature you can imagine. This is simply to say, there was no shortage of great books for Márton to read; and even today, his interest in literature is marked by his wide reading interests.

Márton grew up in the shadow of the Hungarian Revolution in 1956, during which there was a massive popular revolt against the Soviet Occupation. Eventually, the Hungarians were suppressed, but in the interest of preventing another such rebellion from fomenting, the Soviets began a policy of "soft" dictatorship in Hungary, which prevailed until the bloodless transition from Socialist to Democratic state in 1989. (Many other Eastern bloc countries had it much, much worse, including most of Hungary's immediate neighbors.) What this meant to Márton was a relatively clear path through his subsidized education — he received a degree in economics from the University of Economics in Budapest, called Karl Marx University at the time, and access to an active but cloven arts and literature scene, divided between state-sponsored work, and more typically rebellious, underground writings and productions. (Because the state was leftist, the underground in Hungary, as it was in many Eastern Block countries, was somewhat enamored of the West.) It also meant relative freedom to travel. As a young man, he took three separate trips to Paris (where he found himself "lonely and wanting to write"), as well as a lengthy odyssey by train with a friend to Moscow when he finished high school.

Márton's literary activities began, not surprisingly, when he was a teenager, and he began to write "very concrete love poetry," which was not, by his own admission, especially successful. Visiting him in Budapest in 1998, I asked him what had turned him to poetry. He told me then that as a teenager, he began to sense a pervasive feeling of unreality, an alienation in which he was conscious of a veil between himself and reality. Poetry was the only expression that mediated this feeling. Poetry didn't reduce it; but it authenticated the feeling, somehow. Márton has written:

I have two basic states of mind. One is the suffering/confused, when I can't write at all. The other one — which is more exceptional and keeps sometimes only for a few moments — is the happily confused one, when I can somehow cling to the air and enjoy the panorama. But if I write (or more exactly: take) down what I see (which doesn't happen too frequently), the composition generally gets humorous because suffering and confusion are still present and I see myself in the air. The only relief is that I can accept all those contradictions, at least for the moment, and humor is perhaps just accepting contradictions. [10]

Furthermore, as these two states of mind, related I think to his sense of humor and sense of irony, permit Márton to comment on the experience of unreality, they have similarly compelled him toward broken, reduced, and otherwise minimal expressions of that condition, one that, as I've already suggested, represents a simultaneous sense of confusion, suffering, and levity.

It strikes me as useful at this point to propose that Márton's native feeling of alienation, expressed, as he puts it, in terms of a modality of suffering/confusion, and another of levity/accepting contradictions, speaks directly to his Jewishness, as it is figured both culturally and spiritually in his life. Like many Central European Jewish families, Márton's is both assimilated and secularized. He doesn't typically go to synagogue, nor does he maintain any dietary practices. Hungary's Jewish population is large, comparatively speaking: at 80,000, it is much larger than that in any other Central European country. [11] Even so, or perhaps because this is so, for many Hungarians, Márton's Hungarian identity would be defined chiefly by his Jewishness, in spite of his speaking Hungarian, having been born in Budapest, and having lived there his whole life. He is therefore always both things: Hungarian, Jewish. One way to begin to consider this dual but alienating identity is through Eric L. Santner's strong reading of the thought of Franz Rosenzweig and Sigmund Freud in his book On the Psychotheology of Everyday Life. Santner proposes a reflective means for addressing this feeling of alienation, arising, for him out of a native Jewish idiom, "constitutive of the inner strangeness we call the unconscious." He suggests that all people are always internalizing a kind of "uncanny vitality," such that we are

placed in the space of relationality not by way of intentional acts but rather by a kind of unconscious transmission that is neither simply enlivening nor simply deadening but rather, if I might put it that way, undeadening; it produces in us an internal alienness that has a peculiar sort of vitality and yet belongs to no form of life. [12]

Psychoanalytic theory suggests that the psyche is characterized by its excesses, that our somatic-mental complex contains more reality than we are ever able to process. This excess, therefore, requires of us our fantasy lives. "To put it paradoxically," Santner argues, "what matters most in a human life may in some sense be one's specific form of disorientation, the idiomatic way in which one's approach to and movement through the world is 'distorted.' The dilemma of the Kafkan subject — exposure to a surplus of validity over meaning — points, in other words, to the fundamental place of fantasy in human life." Santner concludes that the conversion of fantasy into "more life" is the very thing, at an unconscious level, that holds life together: "If fantasy is the means by which we in some sense place ourselves 'out of this world,' at the 'end of the world,' it is also a means for securing our adaptation to it." [13]

Adaptation. Survival. Security. The dilemma of Márton's Kafkan subject — to borrow Santner's label for the alienated, modern Jew — is mediated through the use of humor and irony that I've described above, a poetic displacement of a scene, a situation, or a piece of language that begins by poking fun, but concludes with a fraught ironizing in which the poet empties the scene, situation, or piece of language of its meaning, but then tries to replace it with the fact of alienation. This alienation functions, borrowing again from Santner, as a fantasy of surplus, as a way of deepening the reality of the poem, strengthening its aura, and providing a means for securing the poet's adaptation to the world he finds himself living in. Take the sequence "Immortality and Freedom," for instance. Here is the text of the poem. (The sequence appears on eleven notecards; tildes indicate breaks between cards. The lines of text appear in the top half of the white field of each card.)

[A sketch-map appears below; to see the poem set out with web equivalents to the

space breaks in Koppány's card, click here]

IMMORTALITY AND FREEDOM

~

a crumpled hope flattened out

~

a crumpled hope flattened out

the later variant

~

a torn hope

stuck together

with visible traces of tearing

~

a torn hope

stuck together

with underlined traces of tearing

~

a torn hope

stuck together

with disguised traces of tearing

plus text

~

an untouched

white hope

~

a hope

replacing

a destroyed hope

~

a hope

reminding of

the irreplaceable character

of a destroyed hope

~

an expectation that something

will happen as one wishes

~

half-crumpled tearings

half-flattened stickings

The impact of this poem is slowed but deepened by its physical presentation: the reader encounters each of these statements at the pace it takes to turn each of the cards over. The poem works as an accumulation, but also as a set of revisions and reconsiderations. What at first appears to be an ironic commentary on Kierkegaard's philosophy becomes something of a midrash on the concept of freedom and immortality, which Márton pins on hope, abjectly defined in the second-to-last card of the sequence: "an expectation that something / will happen as one wishes". Whether immortal or indestructible, hope is given its most commanding presence when modified as "the irreplaceable character / of a destroyed hope". While making few demands of its readers, "Immortality and Freedom," takes on weight in the course of its sequence, as well as in subsequent readings. It's hard not to understand this poem as something essentially sad. But also, in kind with Santner's discussion, as a fantasy, however desolate, that serves to take the surplus of the feeling of alienation and transform it to "more life." In this sense, the poem fulfils one of Santner's claims about "the inner strangeness" of the unconscious, in that it suggests a peculiar form of vitality that belongs uncomfortably to no recognizable form of life.

Mail Art, Milwaukee, English, Lax

"I still respect words."

—Márton Koppány, april 24, 2004

Márton relates that in the 1970s he first encountered the concept of Zen koans, in a series of cartoons published in a Marxist magazine of the human sciences. I take this story as part of the Koppány lore: where better to find the dialogical mode of a sect of Buddhism that would inspire his work than a state-supported sociology journal? He was immediately attracted to the mood and sense of these koans, which were as strange as they were familiar. It's safe to say that Márton was not merely registering an attractive mode in these Zen cartoons; he was also sensing another image of the poet, or the role of the poet, as he regards it. In my mind, I return to Kafka as something of an archetype for this role: the writer who makes out of alienation a terrifying joke whose repeated utterance becomes gradually hymnic. Indeed, it's the luminous effects of repetition, layered in wry humor and humanity, that caused a very similar click of recognition in Márton when he encountered the work of Robert Lax for the first time in the early 1990s. In tracing a path from Kafka, through Zen monks, Hasidic masters, Daoist comedian Zhuangzi (another favorite), Samuel Beckett, to Robert Lax, while we may have covered a lot of territory, we have not altered the persona we are tracking very much. Márton belongs very much in this company, especially in his use of irony, in his relative isolation, and in his deeply humane sense of his alienation.

The event in his literary life that most embodies this alienation is his abandonment of Hungarian for English to write his poetry. This decision is the node into which various strands of his literary and personal activity are joined; it's not, however, one whose meaning is arrived at easily or even consequentially. One way of reading Márton's move away from Hungarian is to think of the advantages he gains by forcing himself into a permanent state of brokenness and reduction in his expression.[14] I think from the beginning, Márton has tended toward the asemic, which means through his poetic career, he has been gradually minimizing the number of signs in his writing. Writing in English, I suspect, allows him to control that minimalizing more than he can in Hungarian, where he is more open to and aware of polysemy seeping into his words. I'm reminded again of Robert Duncan, who, late in his career began to write in French.[15] In a poetry reading, given at the University of California-San Diego, in the 1980s, he explained that he began to write in French because, lacking complete sense of its meanings, he felt more permitted to make poems in a childlike, unencumbered manner.

But Márton's abandonment of Hungarian resonates with other features of his alienated sense of things, as well, particularly his connection (or lack thereof) to the Hungarian literary world, and more pointedly to his identification as a Hungarian Jew. To sound these resonances, it helps to look at some of the developments in Márton's writing life, particularly his three stays in Milwaukee in the 1990s, and how they generated the resolve to convert his poetic self into English. He told me he has given up writing in Hungarian twice, so far: the first time happened in the 1970s, when he was interested in making collages, and had the desire not to depend on Hungarian literature for his inspiration, nor to be victimized by it. (At the time, French was mainly the "other" language he was using in his writings and collages.) He was, by his own account, "completely isolated, almost," having few writer friends and feeling distinctly marginalized through disinterest from any of the alternative art and literary movements of the time. In the early 1980s, Márton became involved with international mail-art, participating in the "circulated" publications that characterize mail-art activities: sending cards, poems, stamps and the like through the mail to various correspondents, themselves linked into similar systems. He came to mail-art almost accidentally. In 1980, a small exhibition of his collages was installed in a one-room gallery that was "checked" by the police, so that the doors remained closed for most of this exhibition. (Márton claims there was no scandal; the doors were simply closed. Presumably, this kind of thing was commonplace, at the time.) However, a Hungarian mail-artist had proved to be quicker than the police and had scribbled something in the guest-book. Márton said this note "opened [his] eyes to the new opportunity." Mail-art had the advantage of being uncensored, ephemeral, and distantly connected. At the same time, according to his account, he "accidentally" met some friends who wanted to publish his work, in Hungarian, in a volume of poetry. Up through the early 1990s, this constituted his self-professed "active period," during which Márton gave readings and regularly attended literary events.

Things changed in the summer of 1991, when Márton and Gyöngyi moved to Milwaukee for the academic year. While Gyöngyi attended to coursework at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Márton experienced his first immersion into English, as well as the pleasures of an American university library system, which allowed him to browse the shelves of the Golda Meir Library unencumbered. (This is impossible to do in most European libraries, public or university.) It was a year of many literary discoveries and lots of reading. It was also the year he made contact with the owners of the Woodland Pattern Book Center, Karl Gartung and Anne Kingsbury. Márton described to me the series of encounters that brought him to Woodland Pattern with a bemused wonder. He had already begun to write sequences in English using the black-bordered postcards. Knowing precious little English but compelled to make connections nonetheless, he went on his second day in Milwaukee to the Museum of Art, in hopes of organizing an exhibit of his work. (He was still thinking of himself as more of a conceptual artist. And presumably imagined that he could walk into a museum and arrange for an exhibition!) By good fortune, the curator he spoke with told him that he should go to Woodland Pattern where he might find people receptive to his work. (In his telling, this curator is very much the hinge on which the fate of this story turns; were she not aware of Woodland Pattern, Márton may not have made this connection, changing this story entirely.) Having felt lonely and isolated in Budapest, Márton was determined to change his perspective in Milwaukee. Arriving at Woodland Pattern, he introduced himself to Karl, who decided, within five minutes of looking at Márton's sequences, to do an exhibition of the cards and to organize a reading/event for them.[16] For Márton, this gesture was a singular opening for his work. How could he not fall in love with America and Milwaukee, or with writing in English? [17]

Though they were in Budapest for the summer of 1992, they came back to Milwaukee for the academic year beginning that fall. Upon returning to Budapest in the spring of 1993, ironically enough, Márton's one book of poetry in Hungarian was published, Bevezetés ugyanebbe (Introduction into this same thing), by Pesti Szalon Kiadó. Regarding its unusual title, Márton e-mailed me this note, wanting to amplify what he had told me in the interview we had conducted earlier that evening, and wanting to correct for me the incorrect title of his book he had written down for me in my notebook:

When writing the book I was looking at my present from the perspective of the future: how I will delete "this" [these] very moment(s) (in Milwaukee in 1991 etc.). And I also

wrote about looking back to "this" present from the future, as if I had been reading myself - many years later, introducing (myself) in "this" [these] very moment(s). (So it was about feeling "versus" reasoning...)

"Today," being on the other side, I mean many years after "this" [these] moment(s), I REALLY can't introduce myself into anything, but THAT. I think my lapse means that I've identified myself with the process instead of the memory of it, which also means that I was right—in a certain sense—12 years ago.

I suspect that his complex relationship to this title of his one collection of poetry published in Hungarian speaks to the fraught nature of that work, even as it is reflects the spare aesthetic that characterizes all of his work. There is a difficulty built into his relationship with the work that feels almost impossible for him to articulate. From what I can tell, Márton's experience of this book is rather neutral, which is to say its appearance didn't dissatisfy him, but it hasn't meant a great deal to him either. I don't think it is as valuable to him as Investigations, collecting some of his works written in English, and published in Tokyo and Toronto by Ahadada in 2003.

Márton and Gyöngyi returned to Milwaukee in the fall of 1996 for another academic year. This time, he reconnected with friends in the city, including Yehuda Yannay and Bob Harrison, as well as connecting with other artists and writers, including Clark Lunberry — whom Márton would eventually publish through Kalligram — Marsha McDonald and Kevin Koenigs, to name a few. (Though some of his connections were gone, including Jesse Glass, one of the publishers of Ahadada Books, who had moved to Japan.) Before returning to Milwaukee, Márton became "absolutely uninterested in publishing anything more in Hungarian." Back in Milwaukee, he resolved to connect with American publishers toward getting some of his work out in the U.S. (And this, as I've said, is why we met in 1996.) By this time, Márton seems to have committed himself to being a poet who writes in English.

Nineteen ninety-six was the year he first encountered the work of Robert Lax, during his meanderings in the library. Since then, Lax has exerted a powerful influence on his own work. In Lax, Márton recognized not so much himself, but a pace of communication native to his own sense of poetry and how its recognitions are revealed. I suspect as well a deep sympathy of character to be shared between the two, in terms of their lifestyles, their outsider status, and the poetic modes they find most expressive. In the summer of 2003, we were looking over some photocopies of Lax in Márton's study. We paused at the poem "river":

river

river

river

river

river

river

river

river

river

river

river

river [18]

I made a joke about how "difficult" this poem must be to translate into Hungarian — Márton has been translating Lax since he discovered the work — but Márton assented to the difficulty. He told me that the genius of the poem is not the repetition itself, but the grouping of "river" into threes, and then knowing to conclude the poem after four such groupings. Physically, the form of the poem could be translated into Hungarian; but can the instinct behind it be carried over? Márton was not so certain. (We should all be blessed with such careful readers! Not to mention such thoughtful translators.)

Márton's "Homage to Robert Lax" characterizes his feelings toward the work in a typical, illuminative fashion. The poem begins with a quote from Karl Young, referring to Lax, which says, " . . . . maybe that's one of the reasons why literati going in other directions don't know what to make of him." Young's statement serves then as the basis for the poem:

lit

er

a

ti

lit

er

a

ti

going in other directions

This poem was written shortly after Lax's death. Lax, like Márton, had always been contemplating the "other side" in his work.

A poem from The Other Side, his collection published by Kalligram in 1999, strikes me as an illustration of Márton's sympathies with Lax, particularly in its minimal gestures toward a natural phenomenon which reveal both an anxiety and a mysticism at work in perception and language. By Márton's standards, "Waves" is a "long" poem, again on postcards, even as it is made up of only seven words, which are repeated. As in other serial poems of his, "Waves" makes use of the longitudinal space of the card, with words appearing near the top, in the middle, and toward the bottom — these differences I have indicated below in bracketed notations. (As with my transcription of "Immortality and Freedom," the tilde indicates a new card):

[A sketch-map of the poem appears below; for its graphic arrangement in the web's equivalent of card sequence, click here]

WAVES

~

a little time to solve it

{top}

~

a little time to accept it

{middle}

~

a little time

{bottom}

~

a little time

{top}

~

a little time

{middle}

~

a little time

{bottom}

~

{blank}

~

{blank}

~

{blank}

~

waves

{middle}

~

waves

{middle}

~

waves

{middle}

The success of this poem hinges on its initial expressions of anxiety — the impending crash of the water on the shore, presented as a problem to be solved and then accepted — transformed into an acceptance represented by the three blank cards followed by the three "waves" cards. What has happened in the space/time of those three blank cards? Is this the water itself crashing? Or is it something like Eliot's "still point," a suspended moment, one either of clarity or of submission? I connect this poem back to my thoughts on Lax's "river" (though Márton's poem owes nothing to Lax's; he wrote it in the 1980s, originally in Hungarian, which was well before he began to read Lax's work and to absorb his influence): Lax's vision in the poem is one that ceases — even as it has been built on identical repetitions; likewise, Márton concludes with the triple repetition of the waves, coming, presumably, to the shore. (Which, of course, is never mentioned in the poem; my sense of the shore is something I've extracted from the implied subjectivity the poem encourages by staging itself as a problem to be solved.) Isn't the tension in Lax's poem, like Márton's, built on the anxiety of its repetitions, which resolve in an acceptance of the thing being repeated? As in the physical world, the poem submits to the flow of language, whether riverine or oceanic.

It is Enough for Me: Life in Budapest

I think Márton would like to be living in Milwaukee still. Circumstances drew both him and Gyöngyi back to Budapest in 1997, including the precarious health of their parents, whom they have cared for into their last days. They have remained in Budapest since. These days, Márton earns his living by translating bestsellers from English into Hungarian. The pay for this task is slight, but the work is steady. It also keeps him connected with the occasional opportunity to translate American poetry into Hungarian, which is sometimes subsidized. (He's recently discovered the work of Armand Schwerner and Michael Heller, for instance, which he has been translating for Kalligram, a literary magazine affiliated with the publisher.) His income is supplemented by a gift his father left him: the deed to his furrier's shop on Király utca. Márton rents the store out to a pair of young women who run a CD shop there. His sense of his community has recently shifted, somewhat dramatically, with the arrival of a very affordable DSL service to his apartment on Bácskai utca. DSL costs the same in Hungary as it does in the US; Hungarians, however, typically make five times less than Americans. Therefore, such services are costly. Because of his affordable, quick, and constant connection, Márton is linked to the small but vibrant world of concrete, visual, conceptual, and minimalist poetry, which has a strong presence online, where the work is relatively simple to reproduce effectively. He said to me that it has changed his life completely, being to read websites without any limitations.

One day in April, 2004, the one during which we were walking around the Margit-sziget in the rain, we came upon one of the numerous pedestals to be found in the park, on top of which you find the busts of famous Hungarians — artists, architects, poets, and musicians. Looking at one of them, Márton said to me, "I will take you to a special place in the Városliget where there are three of these, and I will tell you the story about them." Soon after, walking through the City Park, he showed me the pedestals. They rest, headless, in a corner of the park; a path runs between them. The story is a kind of parable of the New Europe. The three pedestals are supposed to support three busts of three Hungarian writers, two of them Jewish, and one a well-known freemason. (They are Milán Füst, Zoltán Somlyó, and Elek Benedek, the freemason. [19]) Márton says that for years, every time the heads were pulled down by vandals, the city officials would remount the heads. At which point they would be promptly pulled down again. And then replaced. "Until, they finally gave it up, and just left the pedestals."

[Márton in the Városliget, April 2004]

It was after showing me this "monument" that Márton made his comment about tolerance. He said, "It's not so important to me that I be understood, only that I be tolerated. And here in Budapest, I am tolerated. And that is enough." Heading back through the park to the Metro station, we walked by the Széchenyi Baths, where Márton swims twice a week. In the summer of 2003, explaining his schedule to me, he said, "Some of the best moments of my life I have spent swimming." These notions — tolerance and the best, repetitive moments — are, in the end, as clear an expression of the humanizing nature of alienation as I could ever myself express.

After visiting him in the summer of 2003, I wrote a poem for Márton, an effort perhaps to describe some of the experience of being with him in Budapest. My mother's father is Finnish — his family emigrated to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan where he was born. Finnish and Hungarian are related languages, part of the seemingly mysterious, non-Indo-European Finno-Ugric family (which includes Estonian and Karelian, and is somehow distantly related to Korean). I fantasized about a connection, then, to Hungary — somehow. This fantasy is made denser by the Jewishness on my mother's mother's side of the family, which, while already assimilated in London at the beginning of the 20th century, actively suppressed any of its Jewish remnants when my mother's grandfather, Louis Blauman, moved to the Detroit area and began working for the Ford Motor Company, run by notorious anti-Semite Henry Ford, and decided to live in Grosse Pointe, a suburb of Detroit with blue laws against Jews living there at the time. The title of the poem comes from something Márton said to me when we arrived in Budapest that June. He had asked me whether I was planning to do any writing while there. I told him not really, but that I had a notebook with me in which I planned to record the facts of our trip. My title was his — perfectly-pitched — response to this prospect.

What Could Be More Valuable Than The Facts?

for Márton Koppány

Tibetan Buddhism is a dialect of English.

Sanskrit is a kind of English; or a part of its grammar.

Once, I was Jewish. Back in the 1800s.

Once, I was Persian, many centuries ago.

It's my Finno-Ugric roots that ensnare my limbic system in shamanism.

It's the smells of urine & paprika rising from the street — the Way of Kings, the city's oldest.

Religion is when you find a new vowel

in a book

on your tongue.

This poem presumes connections I can't avow to have, neither to a place — Budapest — nor to its language. And especially not to the person to whom it is dedicated. "What have I in common with Jews?" asked Kafka, adding, "I have hardly anything in common with myself and should stand very quietly in a corner content that I can breathe." [20] And what could be more valuable than standing quietly? Or swimming? Or noting something, however transient, down?

[Márton & me in Ráckeve, June 2003]

Go to

Marton Koppány Survey

Go to

Institute of Broken and Reduced Languages

Go to

Light and Dust Anthology of Poetry

|

|

|

|

|